|

|

Surrealism, Sufism and the Zohar

|

||||||||

Author's note: I wrote on the similarities between Islamic Sufism and Jewish Kabbalah in the medieval era for The Huffington Post in a commentary dated Oct. 5, 2011. With the present remarks, I will bring some aspects of the topic closer to the present.

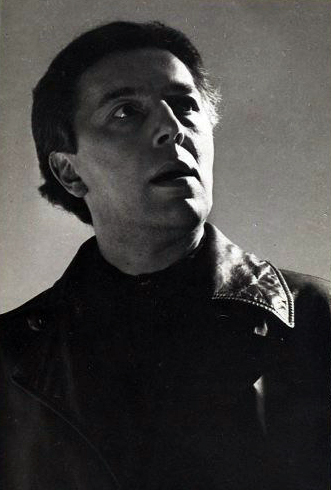

I first learned of the outstanding classic of Kabbalah, the Zohar, in a manner atypical even for this extraordinary topic. Rather than discovering it in metaphysical circles or the Jewish religious milieu, I saw it cited by the French surrealist poet, anti-Stalinist revolutionary, and unapologetic occultist André Breton (1896-1966). Breton was enthusiastic about the Zohar as a source of the "analogical" method for the realization of poetic images. For much of my early adulthood I was devoted to Breton's surrealism.

André Breton, 1896-1966. "I mine the gold of time." |

In 1979, at 31, I first visited Europe, and, still under the influence of surrealism, headed for Paris. There I met the remaining adherents of Breton's movement. I visited the Shakespeare and Co. bookshop on the left bank of the Seine. This was not the original enterprise of the same name established by Sylvia Beach (1887-1962) and associated with publication of James Joyce's Ulysses, but had been launched by another American, George Whitman, who died at 98 in December 2011.

In the legendary upper floor of Whitman's literary monument I saw a red-bound volume on a crowded shelf: The Zohar, by a certain Bension. Its full title is The Zohar in Moslem and Christian Spain, by Ariel Bension (1880-1932), a Sephardic-Moroccan Jew born in Jerusalem. It was published in London in 1932, the year of Bension's death. After my "chance encounter" with the Zohar in the pages of Breton, I had read at the Kabbalistic opus in various editions and selections, long and short, for years. In Bension's book, I was intrigued to find a précis and study of it that appeared immediately more accessible than the five-volume English translation issued by the distinguished Jewish publisher, The Soncino Press, in London in 1931-34. More popular books composed of extracts from the Zohar had seemed equally difficult to me. I asked if the copy in Whitman's shop was for sale, and it was.

Ariel Bension's volume was indeed different from others. It first explained the background of the Zohar as a product of medieval Spanish Judaism, with its strong links to Christian and Islamic metaphysics, then offered a digest of its contents. Rabbi Bension was impassioned in his love for the esoteric Islamic classics in Arabic, particularly the writings of the greatest Sufi sheikh, Ibn Arabi (1165-1240), known as Muhyid'din or "the reviver of religion." And Bension's treatment of the Zohar offered additional "openings" of particular interest to me. I found it in Breton's Paris, and was headed next for Spain. I had read and loved the Spanish Catholic mystics. And I had been interested in Islamic Sufism since adolescence.

Šebilj (fountain), 18th c. CE, Sarajevo – Photograph 2008 by Josep Renalias, Via Wikimedia Commons. |

Rabbi Bension's work continued producing echoes in my life, and does so today. In the 1990s I began travelling to the Balkans, where he had served as a rabbi in the cosmopolitan city of Manastir, Macedonia. In 2007 I had the honor of presenting a paper on Rabbi Bension at an event sponsored by the Oriental Institute of Sarajevo and the Faculty of Islamic Studies of the University of Sarajevo. This was an International Scholarly Conference on "The Place and Role of Dervish Orders in Bosnia-Herzegovina – On the Occasion of the Year of Jalaluddin Rumi – 800 Years Since His Birth." The title of my contribution was "The Last Jewish Sufi: The Life and Writings of Ariel Bension."

Rabbi Bension received a Jewish religious and Kabbalistic education in Jerusalem. He then attended universities in Germany and Switzerland, where he was the first Middle Eastern Sephardic Jew to study. He received his doctorate in Semitic languages at the University of Bern. He completed The Zohar in Moslem and Christian Spain in Cairo. His life was tragically short, but the originality and depth of his writing led to his election as a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of History in Madrid. The book was issued in Spanish, as El Zohar en la España Musulmana y Cristiana, in 1934, with a preface by the philosopher and author Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936).

Unamuno described The Zohar, which combines a midrash, or commentary on the Torah, with dramatic and discursive elements by a group of distinguished rabbis, as something like a religious novel: "it reminds us… of our own Don Quixote," Unamuno declared. As Unamuno linked the Zohar to Don Quixote, I would dare to complete the chain by evoking Joyce's Ulysses, with its shadow hovering over Whitman's bookshop. In all three works, solitary, inspired personalities "go in search of the divine," to borrow Unamuno's description.

Miguel de Unamuno, 1864-1936. |

Rabbi Ariel Bension was a scion of an extremely distinguished school of Arabic-speaking Kabbalists, the yeshiva Beth-El (Beit-El) in Jerusalem. Beth-El gained prominence thanks to the influence of a Yemeni Jew, Rabbi Shalom Sharabi (1720-80). The Kabbalists of Beth-El teach pure concentration on kavvanot, or meditations on the names of the Creator, accompanied by melodies. The resemblance of these practices to the dhikr or "remembrance of God" through recitation, music, and bodily movements by Islamic Sufis is striking.

So too is the historical development through which the Kabbalists of Beth-El became, according to Bension, the dominant school of transcendental religious study among the Jews of the Holy Land. Bension published a Hebrew work dedicated to the man he called "the Master Sharaabi" in Jerusalem in 1930. As described by Gershom Scholem (1897-1982), author of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, first published in 1941, Beth-El "exercised a considerable influence on Oriental [i.e. Arabic-speaking or Mizrahi] Jewry." A more recent study, Shalom Shar'abi and the Kabbalists of Beit El, by Pinchas Giller (Oxford University Press, 2008), similarly emphasizes the influence of the school and its devotion to kavvanot among Jews of Middle Eastern origin.

Yeshiva Beth-El, Jerusalem, 2007 -- Photograph Via Wikimedia Commons. |

The endurance of the "Oriental" Kabbalists, commemorating the names of the Almighty in Jerusalem, and thus reflecting the positive impact of the Islamic environment on Jewish believers, presents a uniquely fecund, but contemporary example of the hidden, vital relationship between Jewish Kabbalah and Islamic Sufism. As in the study of medieval Sufism and Kabbalah, and as eloquently evoked in the writing of Rabbi Bension, this intersection offers a singular possibility for dialogue between the Jewish and Muslim faithful. Muslims, Jews, and Christians who dedicate their lives wholeheartedly to the praise of the Lord of the Universe, Sovereign of the Day of Judgment, may be guided to peace among them. That is, I believe, the common essence of Jewish Kabbalah, Islamic Sufism, and Christian spirituality.

Related Topics: American Muslims, Balkan Muslims, Bosnian Muslims, Macedonia, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Sephardic Judaism, Sufism receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid