|

|

Communism and Religion in Albania – The Longest Night

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The flag of the Albanian Nation. |

Albanians defeated the Italians in Vlona and held the line against Slavic absorption in Kosova and Macedonia. Çamëria is still a lost and passionately-remembered Albanian land. Its Albanian-speaking remnant, probably numbering in the thousands, remains subject to discrimination by the Greek authorities.

But the worst harm to Albanian identity was, in my view, brought about by the Communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha (1908-85), within "narrow" Albania. The dictator, having taken power, was complicit in Titoist Yugoslav atrocities against Albanians. These included the massacre of Albanian Partisans in Tivar in 1945, the brutal extirpation of the resistance movement led by Shaban Palluzha (1871/73-1945), and the equally horrific annihilation, at Belgrade's orders, of the Albanian National Democratic Movement, known by its Albanian initials as LNDSh, and in the popular Kosovar vocabulary as Endeja (ND-ja) or "the ND" in the aftermath of the Tito Partisan victory.

Shaban Palluzha. |

While the Yugoslav regime murdered Albanians en masse, the government of Enver Hoxha attempted their collective spiritual assassination. Notwithstanding Soviet recognition of the brief revolutionary government set up in 1924 by Rev. Theofan Stilian Noli (1882-1965) and Luigj Gurakuqi (1879-1925) – an Albanian Orthodox cleric and a far-sighted Christian Democrat – the Communist movement had struck sparse roots in the country. In its "official" Comintern form, as well as through small Trotskyist groups that have been little documented, Albanian Communism was a slender force – regardless of the participation of 50-100 Albanians in the Moscow-controlled International Brigades that intervened in the Spanish civil war of 1936-39.

Theofan Stilian Noli. |

Luigj Gurakuqi. |

When did the "longest night" of religion under Albanian Communism begin? In pondering this question I am reminded of my close relationship with Gjon Sinishta (1930-95), founder of the Albanian Catholic Institute at the University of San Francisco (USF), a Jesuit institution, and publisher from 1980 to 1994 of the Albanian Catholic Bulletin (ACB) in English and Albanian. Before he died, Gjon renamed the Albanian Catholic Institute in honor of Daniel Dajani, S.J. (1906-46), who was executed by the Communists. Gjon became my "second father" – babai im i dytë – by introducing me to and educating me in Albanian culture, of which I previously knew almost nothing, and guiding me through my own family crises. I worked with him on the ACB until its final issue in 1994 and his death. I am pleased to inform readers of this essay that efforts are underway to commit the entire series of the ACB to a DVD for distribution to libraries throughout the world.

Pope John Paul II with Gjon Sinishta. |

Gjergj Fishta. |

But I acquired from Gjon, while assisting him with the ACB, and later, travelling and working as a journalist and consultant in Albania, Kosova, Macedonia, and Montenegro, certainty that the names Hoxha and his cohort attempted to eliminate from the memory of the Albanian nation were classics. The Catholic intellectuals of northern Albania and Kosova, the Albanian Muslim national resistance fighters, the spiritual babas of the Bektashi Sufi order, and Albanian Orthodox clerics like Fan Noli had laid the foundations for the modern national culture. Personalities of the highest calibre, including Fishta, the Catholic author Ndre Mjeda (1866-1937), Gurakuqi, and Mit'hat Frashëri (1880-1949) had participated in the Albanian Alphabet Congress of 1908 in Manastiri. The Manastiri Congress adopted a Latin-based Albanian script that was an important tool for mass education as well as religious and literary writing.

Mit'hat Frashëri |

Ndoc Nikaj |

Alongside Ndoc Nikaj, as disciples of Fishta in the pantheon of Albanian Catholic writers and commentators of which I learned from Gjon were:

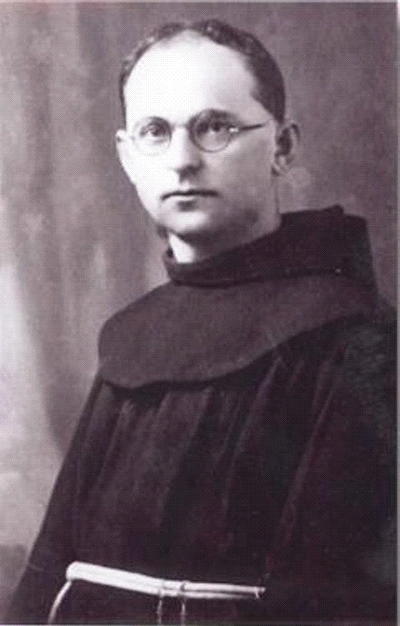

Anton Harapi. |

· At Anton Harapi (1888-1946), publisher for some years of the Shkodran journal Hylli i Dritës (Star of Light).]

Vinçenc Prennushi. |

· At Bernardin Palaj (1894-1947) and his collaborator At Donat Kurti (1903-1983), who achieved lasting distinction with their 1937 collection of traditional ballads, Visarët e Kombit (The National Treasure).

Bernardin Palaj. |

Donat Kurti. |

· At Lazër Shantoja (1892-1945), an outstanding poet.

Lazër Shantoja. |

· At Gjon Shllaku (1907-46), a leading publicist affiliated with Hylli i Dritës.

Gjon Shllaku. |

Martin Camaj. |

Ernest Koliqi |

All these individuals represent a legacy of which any country, large or small, could be proud. But the most important aspect of the "secular" education in Albanian Catholic values and attainments imparted to me by Gjon – since I am not a Catholic myself – had to do with the cluster of death-dates for Nikaj, Harapi, Prennushi, Palaj, Shantoja, and Shllaku. All had been executed by the Hoxha cohort in the bloody purges intended to extinguish the Albanian Catholic intellect forever. I was, and remain, astonished and repelled by the bloodthirsty crimes against the mind committed against Albania. Russia, Romania, Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia – even Communist China – had spared some dissident writers. Some were compromised, some were ostracized, some were reduced to translation or writing for children, but they lived.

Such a development was nearly impossible in Albania, where Hoxha was driven by his egomania and Communist fanaticism to proclaim the country "the world's first atheist state" in 1967, declaring the Catholic, Orthodox Christian, Sunni Muslim, and Bektashi Sufi communities outside the law. Their properties were confiscated and turned over to use as basketball courts, film theatres, and other less-dignified, to say nothing of sacrilegious, destinies. The voices of Albanian faith, patriotism, and progress were kept alive abroad, by figures like Gjon Sinishta and Ernest Koliqi (1903-75) among many other Albanian intellectuals who escaped from Albania and the Albanian territories of the former Yugoslavia.

Rahmetli imam Vehbi Ismail. |

Rahmetli Baba Rexheb Beqiri. |

In a certain way, I owe everything important in my life today to two Albanians who found religious liberty in America: Gjon Sinishta and Baba Rexheb.

The communist regime of Albania persecuted all intellectuals who did not submit to the Communist apparatus during the 1940s. But their main targets were religious figures, especially Catholic priests. The Catholic clergy were highly educated and did not join the Communists. Every Catholic priest had taken at least one course in philosophy during their academically rigorous schooling. They were true intellectuals. With their knowledge, Catholic priests were able to present strong and eloquent arguments against Communist ideology. Communists feared them the most. Therefore, they executed and imprisoned them.

The cultural devastation experienced by Albania exceeded that of North Korea, which claims to preserve its folk traditions in defiance of the alleged "Americanization" of the Republic of Korea. The only Communist country that accomplished a similarly total sweep of its outstanding cultural representatives has been Cuba under the Castro brothers, where since 1959 nearly every significant Cuban writer has been silenced or impelled to escape the island. Few of the bien-pensant fans of Cuban Communism outside Latin America realize that before Castro, Cuba was one of the great Hispanic literary powers. To gullible foreigners, Cuban culture began with Fidel Castro.

Similarly, Enver Hoxha pretended that Albanian culture was born with his reign. As a symbol of such hubris, in one of the most bizarre and abhorrent acts of the Communist regime, the very bones of Gjergj Fishta were dug up and cast into a river. Naim Frashëri and a few other Albanian classics could not be touched by Hoxha's minions, as they were dead and too popular to outrage in the manner inflicted on the remains of Gjergj Fishta. Instead, Naimi was acclaimed as a national poet to replace Fishta, although Naimi's Bektashi verse (Qerbelaja, printed in Romania in 1898, and Lulet e verës (Summer Flowers), were not printed in Albania until after the fall of the Communist order. Migjeni (1911-38) was associated with a Trotskyist, according to Robert Elsie, and I am sure he would certainly have been killed had he lived to see the triumph of Enver Hoxha. Andon Zako Çajupi (1866-1930) would most likely have been condemned as a "bourgeois" author. Asdreni (1872-1947) perished in Romania, obscure and poor. The very great Lasgush Poradeci (1899-1987), one of the finest Albanian lyricists, evaded punishment from the dictator by confining his literary work to translation, as I have indicated other writers in Communist states were compelled to do.

Lasgush Poradeci. |

Further, Gjon published and acquainted me with the admirable and indefatigable writings of the outstanding contemporary foreign scholar of Albanian culture, Robert Elsie. It is amazing and detestable that the group of Catholic writers slain by the Hoxha crew was extended by Elsie, in his authoritative Albanian Literature: A Short History (2005) to include martyrs from all Albanian religious and ethnic communities, including the Arberësh (Italo-Albanian) publisher Terenc Toçi (1880-1945), who Sinishta had memorialized, but also to the Bektashi Baba Ali Tomorri, who wrote as Ali Tyrabiu (1900-47). Elsie went on to name playwrights and other authors who died in jail: Kristo Floqi (1873-1951), Ethem Haxhiademi (1902-65), the Muslim literary personality Hafiz Ibrahim Dalliu (1878-1952), and the poet Gjergj Bubani (1899-1954). Elsie notes with awe that the author Lazër Radi (1916-98) left jail in 1991, when the regime fell, after serving 46 years of imprisonment and internment.

In the years since Gjon Sinishta's passing, I remember him daily, with gratitude for the schooling he provided me. We did much more together, including the foundation of the "Friends of Kosova" in San Francisco. Later I read a book that serves as a companion to The Fulfilled Promise, Dr. Pjetër Pepa's The Criminal File of Albania's Communist Dictator (English edition 2003). Gjon had printed a shocking five-page roster of the Catholic martyrs in his volume. Elsie added information about many of them. But Dr. Pepa presented many more names and details of the victims, drawn from official archives after the end of the Communist tyranny. Dr. Pepa's volume includes candid, court photographs of several figures of whom Sinishta included selected, inspiring images in The Fulfilled Promise.

Dr. Pepa describes the Catholic clergy as "the epicenter of the Communist earthquake" after the second world war. As Sinishta and Dr. Pepa both emphasized – the first orally to me and the second in print – Shkodra and its Catholic clerics, Jesuit and Franciscan, were viewed by the Communists as their most serious adversaries. The first important victim was Imzot Luigj Bumçi, who died of police maltreatment in 1945, three months after Hoxha was installed in power. Imzot Bumçi was the head of the Albanian delegation to the Paris peace conference that concluded the first world war.

Luigj Bumçi. |

Daniel Dajani. |

Gjon Fausti. |

As related by Dr. Pepa, At Fausti repudiated the Communist charges of collaboration with the Axis powers. The priest stated that he considered fascism as bad for Italy as for Albania and the Italian invasion a foreign aggression. But he also insisted on his stand against atheist Communism. At Dajani was accused of participating in publication of a book on "ethnic Albania" – i.e. the country of Albania, plus Kosova, western Macedonia, the Albanian-speaking regions of Montenegro and Serbia, and Çamëria. The prosecutor, Aranit Çela, interrupted him to accuse him of fostering hostility to Yugoslavia, which claimed most of the contested territories.

Dr. Pepa's indispensable, encyclopedic volume encompasses thorough accounts of six other frightful trials by the Hoxha clique. They were:

1. The Special Tribunal of March 1945, in which 60 were accused and 17 ordered executed, including Terenc Toçi (also Italian by birth) and, incredibly, Bahri Omari, the brother-in-law of Enver Hoxha and editor in the U.S. of Dielli from 1915-1919. The remainder received sentences between two years and life imprisonment, with two found innocent.

2. The massacre beginning in 1945 of 20 people associated with the Harry Fultz American Technical School in Tirana, followed by 80 more condemned to imprisonment, with many dying behind bars.

4. The trial of 37 anti-Communist opposition politicians in 1946, of which nine headed by Sami Qeribashi were executed, with the rest jailed for periods varying from a year to life, and two found innocent.

4. The 1947 trial of "the deputies," including members of the National Liberation Movement and legislators elected to the first postwar Constituent and National Assemblies. The chief defendant was Shefqet Beja. Sixteen were condemned to death by hanging or shooting, while four more were jailed for life and four for 20 years. Among those killed was the Bektashi baba Ibrahim Karbunara, aged 67, a colleague of Ismail Qemali Vlona in the 1912 declaration of independence.

5. The 1947 proceeding against the "Riza Dani" group accused of counter-revolutionary activities Of nineteen defendants, seven were executed, six condemned to life in prison, and the others to jail terms of 15 to 20 years. According to Dr. Pepa, most of the victims were caught in the Communist net because of unfavorable family relationships, especially with emigres. They were also alleged to have participated in various terrorist acts. Riza Dani and five others had been elected members of the postwar legislature. Dani was shot by a firing squad.

6. The 1948 execution and punishment by life imprisonment of 18 members of the Catholic hierarchy. Those done to death included Imzot Frano Gjini (1886-1948), Mons. Nikoll Deda (1890-1948), and At Çiprian Nika (1900-1948). Among the others, several perished from the effects of torture. At Donat Kurti (1903-1983), the colleague of At Bernardin Palaj in assembling the precious Visarët e Kombit, was interned, his fate unknown to Gjon Sinishta and others for decades. At Zef Pëllumbi (1924-2007), lived to become rector of the Franciscan Church in Tirana. Dr. Pepa notes that the measures taken against Mons. Gjini, At Donat Kurti, At Çiprian Nika, and At Pal Doda (1880-1951) in this falsification of justice extended to 16 other individuals. Later, Muslim clerics including Hafiz Ali Tare were shot, along with at least four more victims.

Frano Gjini. |

Çiprian Nika. |

But Dr. Pepa's reminder of the charges against Daniel Dajani, S.J., and others – of opposing Yugoslav hegemonism – brings us most directly to the source of Albania's Communist agony. The persecution of anti-Communist and anti-Yugoslav Albanian patriots began, I believe, with the establishment of the previously-illusory Albanian Communist Party, under the direction of two Slav Communists, Dušan Mugoša (1914-73) and Miladin Popović (1910-45), in 1941. The Communist-led Albanian National Liberation Movement was created at the 1942 Peza Conference, with the participation of Popović, but also with the support of independent nationalist resistance leaders such as Abaz Kupi (1892-1976), the Bektashi baba Faja Martaneshi (d. 1947), and Myslim Peza (1897-1984). Of the last three, the valiant and indomitable Abaz Kupi would continue his struggle against Hoxha's minions until his last breath. Baba Martaneshi was killed in a clash inside the Bektashi Kryegjyshata (Supreme World Headquarters of the Bektashi Order) in Tirana in 1947, and Myslim Peza was idealized as a hero of the Communist state.

Abaz Kupi. |

Resolutions favoring the right of Kosovar unity with Albania were adopted at a later conference held by the Partisans in Bujan in 1943, where only a seventh of participants were non-Albanian. But the supreme Yugoslav Partisan chiefs immediately rejected this proposal. Dr. Pepa calls attention to the Mukje Agreement, signed the same year in Albania, to coordinate the activities of the Partisans and the anti-fascist, nationalist Balli Kombëtar (BK), in the Committee of National Salvation. Mit'hat Frashëri was present as the BK chairman at the Mukje meeting, which called for the unification of Kosova and Albania. But the Titoite representative Svetozar Vukmanović (Tempo) (1912-2000) as well as Popović, who according to Dr. Pepa was travelling with Hoxha, objected strenuously to the Mukje Agreement and within days it was denounced by the Albanian Communists.

Thus began the "Albanian civil war" between the pro-Yugoslav, Hoxha-controlled Partisans, on one side, and the free anti-fascist forces including Balli Kombëtar and the liberation movement led by the brothers Gani, Hasan, and Sahit Kryeziu, from Gjakova in Kosova, on the other. All resisted the Axis invaders. Yet the Communists were clearly more concerned to wipe out their competitors within the forces of the national uprising. One of the first victims of Hoxhaite "justice" was, paradoxically, an ex-Communist of Trotskyist and anarchist sympathies, Llazër Fundo (1899-1944), beaten to death by Hoxhaites in the Malësia e Gjakovës between Gjakova and Kukës.

Llazër Fundo. |

Communism was foreign to Albania. The Soviet-directed Communist International hated the interwar monarchist Yugoslav government for sheltering anti-Communist Russians, and therefore assisted the Kosova Committee (Komiteti i Kosovës or K.K.) in the Kosovar anti-Serbian fighting of the 1920s. But in the western Balkans, the Serb-imperialist trend in the Yugoslav Communist leadership had long since abandoned an orientation sympathetic to Kosovars when the Albanian Communist Party was established and Albanians recruited to the Slav-directed Partisans.

Once the Yugoslav Partisans had achieved dominance in the western Balkans, the rest followed inevitably. Hoxha functioned as a loyal servant of Belgrade until the Stalin-Tito split of 1948. After that Hoxha pretended to ferocious opposition to Yugoslav domination and expansionism. But in reality Hoxha did nothing to assist the Kosovar Albanians in their long battle for freedom. The Albanian Partisans at Tivar, the soldiers of Shaban Palluzha, and the National Democratic movement were doomed.

Hoxha and his Slav masters understood one thing very well: for the Albanians to be subdued, they must first be deprived of their religious leaders. Hoxha accomplished this evil end… temporarily. But neither he nor associates could make atheism a permanent feature of Albanian life.

The Communist dictatorship in Albania was not the last to fall. It remains surpassed in endurance by the "first Communist dynasty" in North Korea, which began with Soviet occupation of the northern part of a divided country in 1945 and has recently enthroned a new successor as dictator, Kim Jong Eun. The age of the young tyrant is unconfirmed, but hovers somewhere between 28 and 30. In addition, Communism has lasted in various forms in China, Cuba, Vietnam, and Laos, with aspirants to Marxist autocracy present in Venezuela and other Latin American countries.

To those who have studied the record of Communist misrule around the world, however, it should be clear that the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist-Maoist, and above all, Enverist regime in Albania exceeded others in the intensity of its heartless oppression of its own subjects. Soviet Russia wiped out a generation of brilliant intellectuals, starved to death and otherwise murdered whole classes of peasants, imposed its system on most of its neighbors, and deported entire nationalities to labor camps or detention in Kazakhstan and Siberia.

Yet Russian religious, cultural, and liberal traditions were sustained under the brutality of Communism. Battered, reduced in its artistic stature, physically handicapped and limited to an export-based economy, Russia came out of Communism expecting a rebirth. Unfortunately, Russian imperialism, which remains a danger to the peoples of the borderlands, including Poland, Georgia, and the Balkan zone, also persisted from the tsarist epoch through Communism to the present day.

Whether a Russian renewal has taken place or ever will take place is a matter of opinion. As the leading Russian liberal Aleksandr Herzen (1812-70) wrote in his 1855 work, From the Other Shore: "The (tsarist) revolution of Peter the Great replaced the obsolete squirearchy of Russia – with a European bureaucracy; everything that could be copied from the Swedish and German laws, everything that could be taken over from the free municipalities of Holland into our half-communal, half-absolutist country, was taken over; but the unwritten, the moral check on power, the instinctive recognition of the rights of man, of the rights of thought, of truth, could not be and were not imported." Herzen had expressed his concern that Russian liberation from the Romanovs would introduce the rule of "Chinggis Khan with a telegraph."

Nevertheless, Russian religiosity, liberalism, and aesthetic creativity could not be destroyed. Dissident authors like Anna Akhmatova (1899-1966) and Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) survived, as their greater compatriots in literature, Osip Mandelshtam (1891-1938) and Marina Tsvetayeva (1892-1941) died, the first in prison and the second as a suicide under secret police supervision.

Rahmetli Arshi Pipa. |

Related Topics: Albanian Muslims, Balkan Muslims, Bektashi Sufis, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid