|

|

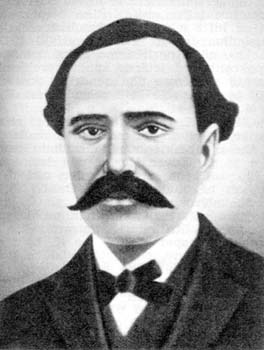

On Faik Beg Konica [1876-1942]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The flag of the Albanian Nation. |

In writing about Albanian Flag Day 2013, I have left aside the history of ethnic expulsions suffered by the Albanians. Still, in homage to the Albanians of Çamëria, I offer part of a long meditation on one of its most remarkable sons, the author, patriot and diplomat Faik Beg Konica.

Faik Beg Konica. |

My thoughts about Faiku bring together several different strands in his biography, and in my own.

The first, which I believe Faiku would have appreciated, involves a book. It is his book in English, Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, published in Boston in 1957 under the auspices of Vatra, the Pan-Albanian fraternal organization, and edited by G. M. Panarity from an incomplete manuscript. Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe is advertised for republication by I.B. Tauris in February 2014.

Pope John Paul II with Gjon Sinishta. |

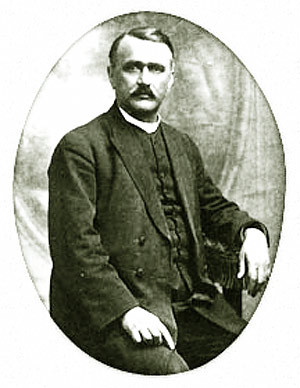

Daniel Dajani, S.J. |

Hearing of my interest, as a news writer then at the San Francisco Chronicle and a contributor to various national magazines, in the crisis of former Yugoslavia, Gjon asked me to help him edit the English section of ACB. In 1990, the first year I did so, he paid me, but after that, until Gjon's death in 1995, I worked for him as a volunteer. (The entire collection of the ACB is now accessible here.)

We became close collaborators and friends – indeed, after the death of my own father in 1992 I considered Gjon "baba im i dytë" – my second father. I did not become a Catholic. Rather, having been brought up without religion, I became a Muslim and Sufi – my first religion.

As Gjon taught me, differences in religion are traditionally subordinate to national identity among Albanians. He began our association by asking me sternly how I felt about Muslims, since it was clear that I favored reconciliation between Christians and Jews. "If you help Albanians, you cannot be prejudiced against Muslims," he said. Gjon demonstrated such a commitment, and while I doubt he could have predicted my acceptance of Islam, two years after his death, I do not think it would have disturbed him.

From left, Monsignor Rrok Mirdita, [Catholic] Metropolitan Archbishop of Tirana-Durrës and President of the Albanian Bishops' Conference; Haxhi Selim efendi Muça, President of the (Sunni) Muslim Community of Albania; Anastas Janullatos, [Orthodox Christian] Archbishop of Tirana, Durrës and Primate of All Albania; Rahmetli Kryegjysh Baba Haxhi Dede Reshat Bardhi, 1935-2011 [Bektashi]. Tirana, 2009. |

Martin Camaj. |

Gjon emphasized that prominent Albanian Muslims, of which Faiku was one, had been educated at the Saverianum. As Gjon put it, "the Jesuits wanted to educate all Albanians, not just the Catholics." Shkodër was and remains the center of Albanian Catholic culture; Faiku himself wrote, in his old age (as translated from French), "the great Jesuit school in Shkodër is like an island in the sea of ignorance dominating Albania."

The banner of Shkodër. |

Guillaume Apollinaire. Photograph by André Rouveyre. |

Next, in the drafty old Main Branch of the San Francisco Public Library, I was astonished to read, in a standard biography, Apollinaire, Poet Among the Painters, by the American academic Francis Steegmuller (1963), nearly the whole of Apollinaire's essay on Faiku. Steegmuller knew nothing of Albanians and was sniffily uninterested in Faiku, referring to Apollinaire's affectionate portrait of him as "at least half invented, probably," although it was almost entirely accurate. (Oddly, Apollinaire described Faiku as "born of a family that had remained faithful to the Catholic religion.") Intimate and important aspects of the relationship are described in my 2004 essay " 'Under Empty Skies Falconers Weep,' " here. (The title of the essay is taken from a poem by the outstanding Yugoslav poet Branko Miljković [1934-61], who repudiated Serbian nationalism and died in Croatia in questionable circumstances.)

Gjon Sinishta was still alive, although close to death from cancer, and he was pleased to hear of my interest in Faiku. The year of my discovery about Faiku and Apollinaire, and of Gjon's demise, saw the commencement of the successful effort to repatriate Faiku's remains from Boston to Tirana.

The burning of the National and University Library in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Hercegovina, 1992, by Serb terrorists. |

It took me 22 years to find a copy of Faiku's Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe. My hunt began before the rise of antiquarian bookselling over the internet, thanks to which I have purchased many books I had tried to locate for years. Faiku's American volume, with its red cloth cover bearing an Albanian eagle on a shield, finally came into my hands in 2012.

I wrote more about my own conceit in considering the relationship of Faiku and Apollinaire as a parallel to my cooperation with Gjon Sinishta, in a small book I published in Shkupi in 2003, Ëndërrimi ne shqip: Dreaming in Albanian. Like Apollinaire, Faiku, Gjon, Martin Camaj and other Albanians I had so far encountered, I considered myself mainly a poet.

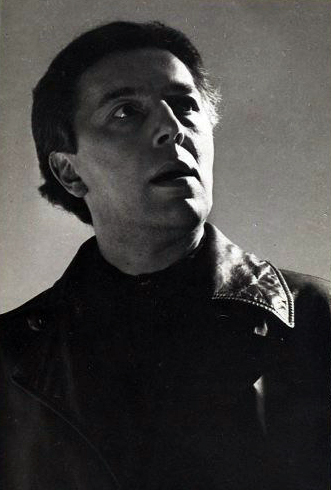

Theofan Stilian Noli. |

Faiku confessed that he had, like the great French novelist Stendhal (Henri Beyle, 1783-1842), a "monomania for disguises," i.e. pen-names, which Faiku confessed was his only thing he had in common with the great French author. I too have indulged in this form of "deception," and I too admit nothing else in common with a figure as great as Stendhal.

The World Headquarters of the Bektashi Sufis, Tirana, Albania. |

But Faiku counted the Bektashis and Laramani, as well as Albanians whose beliefs were folkloric, and the small Protestant community, with the Sunni Muslims, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians, for a total of seven religions in Albania, against those who depicted Albania as an exclusive and conventional "Islamic" society. He did not count, it seems, the small and barely-visible Albanian Jewish community; today, in the aftermath of Communism, he would have to add "non-believers" or atheists to the Albanian religious profile.

The ability to make enemies was a prominent element of Faiku's personality. He came to America in 1909 and took over the editorship of Dielli (The Sun) for Vatra. He became general secretary of Vatra in 1912, but in the previous year had established a journal in St. Louis, Trumbeta e Krujës (The Trumpet of Kruja), of which Apollinaire was informed but which lasted only three issues. The devotion to high-minded, ambitious, and optimistic literary enterprises that prove unfortunately ephemeral is a factor that makes me feel close to Faiku. Gjon Sinishta's tenacity in producing the Albanian Catholic Bulletin illustrates it. But that is a different matter, finally, and extends through world literary and political history.

Ismail Qemali Vlora. |

He served the justifiably-despised Esad Pasha Toptani [1863-1920], a Serbian puppet. Later, Faiku was Albanian ambassador to the U.S. for King Zog [1895-1961], whom he detested and denounced as a coward after Zog fled the Italian fascist invasion of Albania in 1939. With that act by Mussolini, Faiku's diplomatic status in the U.S. ended. Typically of him, Faiku was proud that during his tenure as editor of Dielli and ambassador of Zog to America, he filled the paper with attacks on the monarch.

Now that I have read Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, I cannot but agree with his judgment that modern society is beset by "our mania of thrusting into the face of the public alleged information on subjects of which we happen to be totally ignorant ourselves. Such thoughts sometimes must have occurred to everyone who has an accurate knowledge of something or other and suddenly has stumbled upon a fantastic bundle made up partly of approximations and partly of mere inventions, and not presented by any means as a fairy-tale but as 'information' on the subject in question. That is especially the case with the treatment of distant countries."

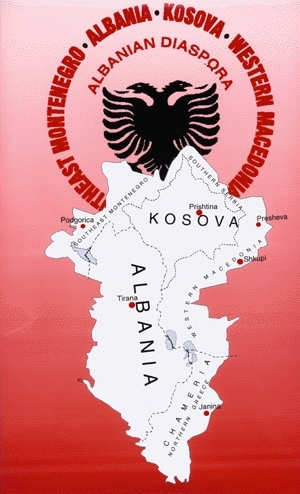

Ethnic Albania. |

Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe includes notable examples of wit at the expense of Serbs and Greeks as the two long-standing aspirants to the partition of Albania. Faiku recalls that Serbs had fled the Ottomans by emigrating into Vojvodina, a part of Hungary, and that "two or three centuries later the descendants of these refugees, who were the beneficiaries of this hospitality, petitioned the Powers [successfully, I should add – SAS] to give over to Serbia the sanctuary of their ancestors."

18th-19th c. CE Haxhi Et'hem Beu Mosque, Tirana – A most precious jewel of Albanian sacred architecture, subsidized by a Bektashi Sufi shahid. Photograph 2007 Via Wikimedia Commons. |

Faiku's book, intended for an American audience, also includes fascinating observations of his people. He cites an Albanian axiom, "Kill me but do not insult me," that I had heard many times during the Kosova independence struggle, most notably ascribed to the human rights activist Adem Demaçi. Faiku describes an area of Albanian folklore previously unknown to me, that of analogical similes, or riddles, such as the following: "What is this? Two brothers hold fire in their hands and are not burned? Tongs."

In a book that while short and left unfinished, is replete with proof of extraordinary erudition, Faiku informs us that the Muslim pirate who captured Miguel de Cervantes [1547-1616], author of the Castilian classic Don Quixote, was an Albanian called Arnaut Mami (Cervantes was held as a slave for five years.) But in chapter VI of Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, which deals with Gjergj Kastriot Skenderbeu and was completed by the editor Panarity, Fan Noli is the source of observations that "An Albanian could not be a slave… Nobody in the slave markets of Turkey would buy an Albanian… because they were impossible to handle and too dangerous for their masters."

Skenderbeu. |

Prejudices against Albanians persist today because of what Faiku calls the "hypnotism of repetition." At the beginning of the 20th century, a French parliamentarian labelled the Albanians "murderous nomads," and a similar vocabulary is applied today by the producers of the recent "Taken" series of action films, depicting Albanians as kidnappers, sexual traffickers, and generally as heartless criminals.

We also find in Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe a criticism of the Albanian national writing system adopted by the 1908 Alphabet Congress at Manastir in Macedonia. Faiku – too harshly, I think – condemned the 1908 orthographic standard as "cumbersome spelling, which, in its effort to represent every phonetic shade, gives often to the words a repellingly complicated form." I have found that non-Albanians are put off by the complexity of Albanian spelling – but no good thing can be attained without labor, and the task of learning to read Albanian provides more than enough reward for the effort required.

Faiku's "American book" additionally discloses a "secret" of Albanian literature: the poetry of the 19th century Muslim author Hasan Zyko Kamberi (specific dates of life and death unknown), including his "scurrilous" and "licentious" writings (in Faiku's characterization). These include "The Bride's First Night," which Faiku considered "offensive" enough to be unprintable. The present-day Albanologist Robert Elsie, in his authoritative 2005 handbook, Albanian Literature: A Short History, presents "The Bridal Chamber," his translation of the Albanian title "Gjerdeku," as "a realistic account of the anguish and hardship of young women married off according to custom without being able to choose husbands for themselves." But Elsie notes that Kosovar critic Mahmud Hysa, as late as 1987, censured "at times degenerate eroticism" in Kamberi's verse. Faiku and Elsie agree that the most important and popular of Kamberi's poems is his "Paraja" (Money), which attacks greed and corruption.

Kostandin Kristoforidhi. |

In Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, Faiku found opportunities to praise Kostandin Kristoforidhi [1827-1895] of Elbasani, for his monumental Albanian-Greek dictionary. Faiku applauded the Catholic epic poet Gjergj Fishta [1871-1940], author of Lahuta e Malcís (The Mountain Lute, definitive edition 1937) and, with Naim Frashëri, one of the two national poets of the Albanians, as well as two other Catholic authors, Dom Vinçenc Prennushi [1885-1949] and Ernest Koliqi [1903-75]. He recommended the work of Andon Zako Çajupi [1866-1930], Filip Shiroka [1859-1935], whose poems Faiku published in Albania, and, of course, Noli.

Gjergj Fishta. |

Vinçenc Prennushi. |

Ernest Koliqi |

Surveying Faik Beg Konica, and given my appreciation for his friendship with Apollinaire, I would be remiss in failing to note the irreplaceable importance of Luan Starova's previously-mentioned study of the friendship between the two men, Une amitié européenne: Faik Konitza et Guillaume Apollinaire. When I wrote, touching on the link between these two literary pioneers, in Ëndërrimi ne shqip: Dreaming in Albanian, I was informed only by Apollinaire's own essay and Steegmuller's biographical research on him. Starova's book, of which I did not know, had already been in print for five years, but titles on Albanian topics do not always circulate as widely as they should. Books on the Balkans printed elsewhere arrive in the region quickly; books produced in the peninsula are unable to be found outside their countries of origin.

Because of this, only after reading Starova's work could I appreciate Faiku's remarkable polemic against the appeal of artificial "universal" languages like Esperanto, titled Essay on Natural Languages and Artificial Languages, signed with the pen-name "Pyrrhus Bardhyli" and published in 1904 in Brussels. Esperanto, in particular, was (and still is) promoted by social reformers who viewed "competing," diverse languages as a cause of conflict, and saw in an artificial, international idiom a means to attain peace. But as someone who learned Catalan – a minority language in Spain – before studying Albanian, who has defended the internal diversity of Albanian (Gegnisht, letrare, Elbasani dialect, Toskërisht), and who appreciates the preservation of differing literary traditions in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, I agree with "Bardhyli." The human inventory of languages and dialects should be preserved and defended, not suppressed or surrendered to a single planetary form of speech, especially in the name of social harmony.

The author of this article inspired by a visit to the great Franciscan Library, where Gjergj Fishta wrote Lahuta e Malcís, in Shkodër, Albania, 2012. |

In 2003, however, I had not yet found Starova's book, and wrote accurately but wrongly that I was "unable, so far, to locate any reference to this work or to the latter pseudonym [Pyrrhus Bardhyli], in Faik Konica's works or biographical studies of him." I had also yet to read two literary creations by Faiku that Apollinaire singled out for praise: "Outline of a Method of How to Succeed in Winning Applause from the Bourgeois" and "The Most Colossal Mystification in the History of the Human Species." These appeared in French, in Apollinaire's magazine Le Festin d'Ésope.

Alfred Jarry [1873-1907], founder of French modernist literature and member of the circle of Faiku and Apollinaire. |

"Outline of a Method of How to Succeed in Winning Applause from the Bourgeois" is a brief commentary on how to perform on various musical instruments, recite poetic or dramatic works, produce opera, and otherwise satisfy the Parisian public. It includes careful advice on what to expect from friends planted in the audience (known as a "claque") as well as from critics. It is only marred by its concluding, gushing, and, according to others who knew Faiku, completely sincere devotion to the compositions of Richard Wagner – whom I despise and about whom I would have quarreled heartily with Faiku. Thus, like Ismail Qemali and others, I would doubtless have earned the ire of Faiku – sometimes, it seems, an honor.

Starova has performed other services with his book. He identifies the occasion which brought Faiku and Apollinaire together – a discussion by Apollinaire in a French journal of attempts to remove French words from the German language, in 1903, 110 years ago. Starova elucidates the origin of the curious pen-name – Thrank Spiroberg – with which he launched Albania, and which Apollinaire mentions in his biographical sketch of Faiku. The pen-name, originally "Trank Spirobey," was borrowed from that of an Albanian hero in a novel by a French Orientalist and travel chronicler, Léon Cahun [1841-1900], Hassan Le Janissaire (1891), and, as it happens, one more favorite author of Apollinaire. To further "protect himself," Faiku made the pseudonym less "baroque" by adding an "h" and an "r," when creating Albania. In other of the many coincidences we find in the neglected area of Balkan relations with Europe, Léon Cahun was the uncle of a different friend of Apollinaire, the French experimental writer Marcel Schwob [1867-1905[, and great uncle of a leading member of the French surrealist circle, Claude Cahun [1894-1954].

Andre Breton [1896-1966], founder of the French surrealist movement. |

Faiku's correspondence with Apollinaire is excerpted in a tantalizing way in Starova's contribution. One letter from Faiku refers to an alleged invitation, previously known to scholars, for the French poet to occupy a well-paid academic chair in Salt Lake City, Utah!

Finally, the work of Luan Starova republishes several articles Apollinaire himself wrote in support of the Albanian national movement. Starova argues for Faiku as a protagonist in Apollinaire's fiction, most importantly in one of two drafts of his novel La femme assise (Seated Woman, published in 1920, posthumously, since Apollinaire died in 1918 during the "Spanish influenza" epidemic, after a head injury suffered while serving in the French army during the first world war). Starova points out that the hero of the second, superior draft of La femme assise, named Pablo Canouris, is identified as half-Albanian and half-Spanish, "born in Málaga" -- fusing two of Apollinaire's closest friends, Faiku and Pablo Picasso [1881-1973]. The book's title is that of numerous works by Picasso and his predecessors and contemporaries, such as Henri Matisse [1860-1954].

The flag of the region of Andalucía, in which Málaga is located. Note the Islamic green, which is unique in European official vexilollogy. Fatiha for the Muslim martyrs of Spain, and honors to the shaykh ul-aqbar of all Sufis, our beloved Muhyid'din Ibn Arabi, may his mystery be sanctified, qaddas sirat'ul aziz. He was born by the grace of Allah subhanawata'la in Murcia under Muslim rule, 1165 CE, d. Damascus 1240 CE. His shrine is currently endangered. |

Faik Beg Konica and Pablo Picasso, Albania and Andalusia, Balkan independence and the artistic avant-garde, united by the pen of Guillaume Apollinaire! Unfortunately, La femme assise has never been translated into English, and as described herein, Faiku's writing in English has been difficult to find. A fresh reading of Faiku, and a reexamination of his life, is overdue. One might even say that those who love books as they once were, rather than electronic novelties, have old but new challenges awaiting them. I fear the internet has been useful in locating, but not in producing, valuable books.

We Are One. The Center for Islamic Pluralism presents this article to the public on the coincidence with the American Thanksgiving, recognizing the Lord of Worlds and divine beneficence to humanity. Further, we celebrate the Albanian example of religious harmony. |

Related Topics: Albanian Muslims, American Muslims, Balkan Muslims, Bektashi Sufis, European Muslims, Macedonia, Montenegro, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Sephardic Judaism, Shiism, Turkish Islam receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid