|

|

The Life and Martyrdom of Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi-Kryeziu, O.F.M.

|

||||||||||||||||

The flag of the Albanian nation. |

Coincidence – "objective chance" as it was called by the great French surrealist writers – plays a fascinating role in spiritual and intellectual life. On January 21, as I was thinking about the life of Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi, O.F.M., I waited for a bus travelling through San Francisco – the city named for St. Francis. When it arrived and I climbed aboard, I saw some young men wearing brown Franciscan robes. They were Americans. I approached them and told them, "God bless you. I am preparing to write about a great Franciscan figure, but I am afraid you will never have heard of him."

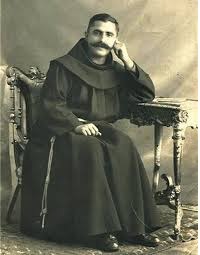

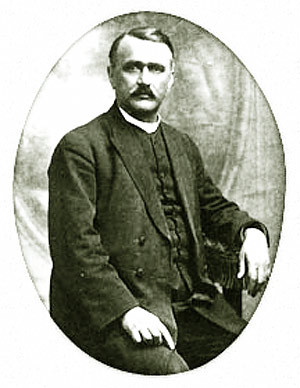

Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi. |

When they asked who the person might be, I said, "his name was Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi, and he was an inspiring Albanian educator and folklorist. He formalized the study of customary law."

I continued, "Among Albanians the Franciscans are known as leading enlighteners. But as Holy Father Pope Francis has been informed, many were martyred by Communism. Friends of the Albanians who are not Catholic, like me, support their canonization. I also hope for the canonization of Father Gjeçovi, a Kosovar Albanian who was murdered by Serbians." They did not know his name but appreciated my comments about the work of their order among Albanians.

And thus the Franciscan identity of Shtjefën Gjeçovi came alive for me, by coincidence, on public transport in San Francisco.

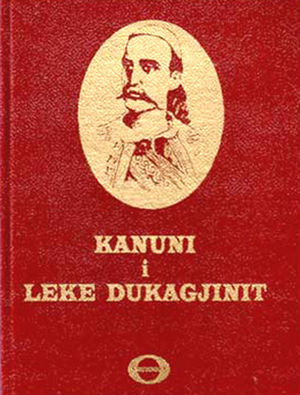

When I consider the life of Shtjefën Gjeçovi I am drawn to the copy of Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit in its 1989 Albanian and English version, edited by Father Gjeçovi, translated by Leonard Fox, and holding a prominent place among my books. But I return equally to memories of Janjeva, the town in Kosova where he was born. Janjeva is a special place. When I visited it in 2000, following the Kosova Liberation War, the Catholic priest who ministered at the church there was still a Croat, representing the then-majority of the town's population. I was told that Croats were leaving Kosova for Croatia, not out of fear of Albanians, but to collect pension benefits that were otherwise unavailable to them.

Memorial to Father Gjeçovi in his birthplace, Janjeva, Kosova, |

Janjeva is distinguished by its history as a mining center with links to Novobërda and Dubrovnik. As part of the silver trade route, it might have hosted some Jews – Novobërda has a large Jewish cemetery, but unfortunately remains the object of Serbian aspirations to recapture and partition the Kosova Republic.

Regarding Shtjefën Gjeçovi, I further recall the bust of him in the courtyard of a Catholic church in Gjakova, Kosova – I believe it is Shën Ndou. His image has the prominent mustache that most Albanian Catholic priests of his time grew. My "second father," the Albanian Catholic writer Gjon Sinishta [1930-95], who introduced me to the work of Shtjefën Gjeçovi, told me an amusing story about the importance of mustaches for priests at the beginning of the 20th century. A young Catholic priest had been sent to Theth, in the high mountains of northern Albania. But after a brief period he was rejected by the congregation there, because, the local folk said, "his mustache was not big enough."

Pope John Paul II with Gjon Sinishta. |

Shtjefën Gjeçovi was educated at Franciscan schools in Shkodra and Bosnia, entered the Franciscan order in 1888, and was ordained as a priest in 1896 at Kresheva in Bosnia, where he finished his study of theology. In Albania and Kosova, he distributed books in Albanian, when such activity was prohibited by the Ottoman authorities. He supported severe sanctions on Albanians collaborating with the Turkish government in 1906, and joined the national uprising of 1912.

Raising of the Albanian independence flag, Vlora, November 28, 1912. |

Naturally, Shtjefën Gjeçovi is known best for his work on the Kanun of Lekë. Obviously, no foreign visitor can comprehend Albanian culture without reading about – or better, studying – Kanun. The authoritative Albanologist Robert Elsie, in his Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture (London, Hurst, 2001) identifies three codifications of Kanun in addition to that of Lekë: the Kanun of the Mountains, used in the highlands above Shkodra to Gjakova, the Kanun of Labëria, from southern Albania, and the Kanun of Skënderbeu, with adherents in north central Albania. But as Elsie points out, that of Lekë is most famous.

Elsie describes the ministry of Shtjefën Gjeçovi in northern Albanian villages, including Laç, Gomsiqe near Shkodra, Theth, and Rubik in Mirdita. There, Elsie tells us, Shtjefën Gjeçovi began documenting oral traditions, tribal justice, and other items of folklore. The Albanian Catholic Bulletin, created by Gjon Sinishta, published an article in 1990 in which Franciscan Father Vinçenc Malaj [1928-2000] portrayed the life of Shtjefën Gjeçovi in those days as one of "numerous calamities and misfortunes." Father Gjeçovi first published sections of his redaction of the Kanun of Lekë in the magazine Albania, issued in Western Europe by the outstanding Albanian author and diplomat Faik Beg Konica [1875-1942]. Here too, "objective chance" plays a role, in that Faiku was a friend of the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire [1880-1918], inspirer of the surrealists. Apollinaire contributed to Albania, in one of the most fascinating and neglected chapters of modern literary history.

Faik Beg Konica. |

Guillaume Apollinaire. Photograph by André Rouveyre. |

More excerpts from the Kanun of Lekë were printed in Hylli i Dritës (Star of Light), the distinguished Franciscan periodical founded in Shkodra by Father Gjergj Fishta [1871-1940] in 1913. Later, Hylli i Dritës was edited by the Franciscan Father Anton Harapi [1888-1946], one of the most prominent victims of Communist oppression in Albania, and by Harapi's brother in agony, Archbishop Vinçenc Prennushi [1885-1949].

Fr. Gjergj Fishta |

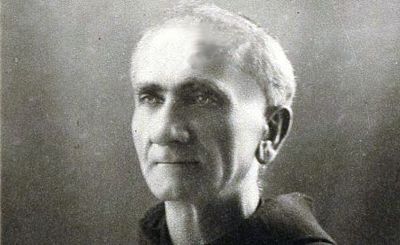

Fr. Anton Harapi. |

Archbishop Vinçenc Prennushi. |

Unlike the modernism of Faiku and Apollinaire, the Kanun of Lekë is a pre-modern document. Similarly, the sacrifice of Shtjefën Gjeçovi came about not because of the claims to enlightenment of the Communists, but as an act of Slav criminality in Kosova. Shtjefën Gjeçovi was murdered in Zym by supporters of the Yugoslav royal dictatorship on October 14, 1929.

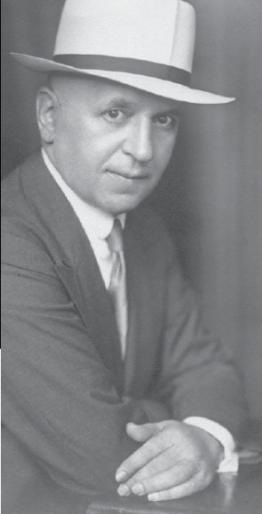

Daut Dauti. |

Kanun has been described by my friend and colleague, Daut Dauti, in his "Ancient Public Deliberation and Assembly in the Code of Lekë Dukagjini," [see Marin, Ileana, ed., Collective Decision Making Around the World: Essays on Historic Deliberative Practices, Dayton, Kettering Foundation, 2006], as "an ancient unwritten code of justice and governance that functioned as the de facto Albanian Constitution for centuries." Dauti commented about Albanian highland culture, "The younger generations were encouraged to value the deeds and the sayings of the elderly as if they were their own." He offered this observation in a paper titled "The Influence of Ottoman rule on Albanian political sociology," presented at the Indiana University-Bloomington Conference, "The Turks and Islam," on September 12, 2010, and published by the Center for Islamic Pluralism and Illyria.

But we should not romanticize the legacy of Kanun excessively. Kanun exemplifies customary law in an age when civil law is triumphant, and the latter is rightly so. Kanun has been blamed for the perpetuation of blood feuds in Albania, and its treatment of women is not acceptable. But it also consecrates protection of the guest, which was the basis for the rescue of Jews in Albania during the second world war. Like many other vital features of human existence, it is contradictory, with bright and dark sides.

Martin Camaj. |

Finally, I open the pages of the Kanun of Lekë in Albanian and English and read its introductory essay by the superlative Albanian poet of recent times, Martin Camaj [1925-92]. I was introduced to Martin Camaj by Gjon Sinishta, and Martin became another important mentor for me. Camaj indicated that Kanun had been reinforced as an alternative in northern Albania to Islamic law, after the Ottoman conquest of the country, and thus, "the highlanders governed themselves for at least 500 years." Crucial details of Shtjefën Gjeçovi's life recounted here are memorialized by Martin.

To emphasize, I am not a Catholic. But like all admirers of the Albanians I yearn for the canonization of Blessed Mother Teresa. Still, as I said to the Franciscans on a bus in San Francisco, when Pope Francis begins examining the cases of the Albanian Catholic martyrs, I hope fervently he will place Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi, O.F.M., at the head of the list for beatification.

Related Topics: Albanian Muslims, Balkan Muslims, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Shariah, Shiism receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid