|

|

The Dayton Accords at 20

|

||||||||||||||

The flag of the Republic of Bosnia-Hercegovina. |

The flag of the Republic of Croatia. |

The Dayton accords, formally signed in December 1995, have reached their twentieth anniversary. Dayton is commonly portrayed as a "peace agreement" for war-torn Bosnia-Hercegovina and an outstanding achievement of Bill Clinton's administration. The accords were an achievement; the war ended. Yet close scrutiny reveals a shabby aftermath.

The Dayton negotiations halted combat between Bosnian Muslims (many of whom prefer to be identified as Bosniaks rather than by religion), Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats. The war began in the spring of 1992 and was mainly fought between Serb aggressors and Bosniak defenders, with the Croats ambivalent allies of the Bosniaks.

The country's people were victims of Serbia's effort to establish a "Serb Republic" within Bosnia-Hercegovina, after the latter was recognized as independent by the United Nations. At the time, census figures showed Bosniaks made up a plurality of the population, 43.5 percent, while Serbs accounted for 31.2 percent, and Croats 17.4 percent. The Serbian forces chose to correct demographic realities unfavorable to them by "ethnic cleansing," meaning mass murder, expulsion, and cultural vandalism. Numerous mosques, Catholic churches, libraries, and other historic structures were destroyed by Serbian troops.

Burning of the National and University Library of Bosnia-Hercegovina in Sarajevo, by Serbian rocket attack,1992. |

The Bosniaks held out almost four years, with significant disadvantages, particularly in heavy weaponry. At least 60,000 Bosniak and Croat soldiers and civilians were killed, with losses of some 25,000 on the Serbian side. The military imbalance was aggravated by a weapons embargo imposed by the United Nations on the poorly equipped Bosniaks and Croatians and the well-armed Serbs. The number of refugees and internally displaced people rose to 2.6 million—out of a prewar population of 4 million Bosnians.

The Serbian assault was planned outside Bosnia-Hercegovina, by Serbian president Slobodan Milošević in Belgrade, with the assent of Croatian president Franjo Tuđman. This continued even as Serbia waged war against Croatia beginning early in 1991. Slovenia and Croatia had by then departed the Yugoslav state, which had begun to disintegrate with the unraveling of communism in Europe. Serbia struck Slovenia first, but the fighting lasted only 10 days and took fewer than a hundred lives. Since Slovenia had no common border with Serbia, it is questionable whether Belgrade was ever serious about holding onto it.

The Croatian war was different—longer, crueler, and more destructive. Croatians inside and outside Bosnia were divided. Many supported an opportunistic deal with Serbia to partition Bosnia-Hercegovina, while others mounted a Bosniak-Croat common defense against Milošević and his Bosnian agents.

In the global media, a "peace conference" was viewed as urgent after the massacre of 8,000 Bosniak men and boys by Serbs at Srebrenica in occupied eastern Bosnia in July 1995. The Bosniaks had been promised protection by the United Nations, but Dutch troops handed them over to the Serbs. A flurry of diplomacy led by U.S. special envoy Richard Holbrooke led to the Dayton accords, signed by Milošević, Tuđman, and Bosnian president Alija Izetbegović—underlining the fact that the Bosnian war was a product of foreign interference rather than internal struggle. Instead of peace, Dayton imposed a truce—or, in the phrase that has come into vogue since last year's Russian invasion of Ukraine, a "frozen conflict."

Dayton came about just as combined Croat and Bosniak forces were beginning to rout the Serbian occupiers from northern Bosnia. Nevertheless, the accords rewarded the Serbs for their onslaught on Bosnia-Hercegovina—and richly so. Less than a third of Bosnia's inhabitants, the Serbs were granted 49 percent of its territory. This corresponded roughly to the areas the Serbs had seized, ethnically purged, and reorganized as a "Republic of Serbs" (RS).

General Atif Dudaković, commander of the 5th Corps, Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Hercegovina, and hero of the counter-offensive against the Serbian forces in northern Bosnia, directly preceding Dayton. |

General Ante Gotovina of the Croatian Army, commander in the north Bosnian operation of 1995. |

Under Dayton, Bosnia-Hercegovina consists of two distinct entities—the RS and a "Federation of Bosnia-Hercegovina" (FBiH). This federation groups areas where Bosniaks and Croats successfully defended their communities against the Serb raiders, including an informal Croatian "third entity" that existed before Dayton. There is also the "neutral" district of Bčrko, in northeast Bosnia, which borders and is jointly administered by both the RS and Croatia.

Dayton thus produced a patchwork rather than restoring Bosnia's unity within borders that were essentially stable from the 18th century till 1992. Bosnia today has three flags, three educational curricula, three police forces, and two systems of postage and customs. The Bosnian presidency comprises rotating Bosniak, Serbian, and Croatian members.

Dervo Sejdić. |

Jakob Finci, Sarajevo, 1998 -- Photograph by Stephen Schwartz. |

Dayton established that Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats are the constituent nations of the country, with others, including children of mixed marriages, excluded from high positions. This discriminatory principle was challenged in 2006 by Dervo Sejdić and Jakob Finci, the first a Bosnian Roma and the second a Bosnian Sephardic Jew. Finci, who also represents the Jewish community on the Bosnian Interreligious Council, served as Bosnian ambassador to Switzerland. In 2009 the European Court for Human Rights found in favor of Sejdić and Finci, but no action to apply its decision has been taken in Bosnia-Hercegovina, which remains politically segregated.

All significant decisions about Bosnia-Hercegovina are made in the Office of the High Representative. The high representative—a functionary of the European Union—is currently Valentin Inzko, an Austrian of Slovene background. Bosnia-Hercegovina is now an effective colony of Brussels.

The 16th c. CE Hadži's or Vekil-harč Mosque in Sarajevo, where the 18th c. CE Bosniak rebels against foreign rule, the beloved Morić brothers, are buried. Fatiha. -- Photograph Via Wikimedia Commons. |

These policies have been disastrous for Bosnians. According to the CIA World Factbook, Bosnia-Hercegovina had an unemployment rate of 43.6 percent in 2014, although the "actual rate is lower as many technically unemployed persons work in the gray economy."

Perhaps, but many Bosnians believe the rate of joblessness is actually as high as 60 percent, reflecting the sluggishness of the private sector. Numerous Bosnians supplement their income from work, pensions, or payments from a diminished social safety net by relying on relatives who work abroad or farm. The CIA World Factbook sums up this grim picture: "Bosnia has a transitional economy with limited market reforms. The economy relies heavily on the export of metals, energy, textiles and furniture as well as on remittances and foreign aid. A highly decentralized government hampers economic policy coordination and reform, while excessive bureaucracy and a segmented market discourage foreign investment."

In the capital, Sarajevo, tensions are palpable. The Bosnian Serb president is Milorad Dodik, whose party, the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats, flaunts the slogan "Dayton forever!" This is understandable, since Dayton gave the Serb militants so much. On October 18, Dodik told an interviewer that "today you couldn't find one person in RS who does not think it inevitable that one day RS and Serbia will be the same in state-legal and political terms."

Behind this renewed Serbian determination, three factors are at work. RS leaders use nationalist baiting of the Bosnian Federation to quell discontent in the RS and promote an artificial Serb unity. Second, on October 29, Aleksandar Vučić, prime minister of Serbia proper, met in Moscow with Vladimir Putin. The Russian assured him of further support for what Vučić called Serbia's "liberty-loving spirit." Finally, Serbia began negotiations for full membership in the EU last year—an option that appears impossible for a partitioned Bosnia-Hercegovina, although the latter did enter the Schengen zone for visa-free travel in 2010.

To add to its woes, Bosnia is suffering a brain drain, reflecting both the high quality of its educational system, inherited from its pre-1918 Habsburg rulers, and the hopelessness of its graduates. Bosnian Croats have the option of taking Croatian citizenship and enjoying the advantages of membership in the EU, to which Croatia acceded in 2013. According to political scientist Florian Bieber, writing in 2011, "hundreds of thousands of citizens of Bosnia-Hercegovina [held] Croatian citizenship as a result of their ethnic Croat identity," and Dodik and other prominent figures in the RS had applied for passports as citizens of Serbia proper. Only the Bosniaks have no legal path to Europe.

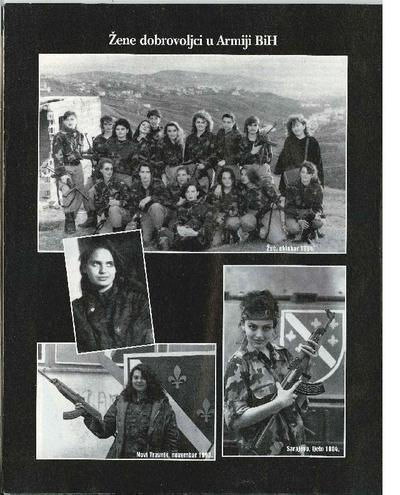

Title: "Women Volunteers in the Army of Bosnia-Hercegovina." |

Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial and Cemetery for the Victims of the 1995 Serbian Genocide Against Bosnians – Photograph 2008 Via Wikimedia Commons. |

The Dayton accords halted the Bosnian bloodshed, but beyond that they failed. Throughout the war, Republican leaders in America called for intervention to assist the Bosniaks and Croats against the Serbs—at the very least, for a lifting of the U.N. arms embargo. Sen. Robert Dole of Kansas was among the most active in this advocacy. In Britain, Margaret Thatcher supported Bosnia even after she left office; the headline on her piece in the New York Times of August 6, 1992, was "Stop the Excuses. Help Bosnia Now."

Dayton did not dissuade Milošević from repeating his atrocities in Kosova in 1998-99. Only heavy NATO bombing stopped him. Dayton was far from a shining achievement. As the presidential contenders clash over foreign policy, its dismal legacy should be remembered.

Stephen Schwartz is a Shillman/Ginsburg writing fellow at the Middle East Forum.

Related Topics: Albanian Muslims, Balkan Muslims, Bosnian Muslims, European Muslims, Kosovo, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Sephardic Judaism receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid