|

|

Who is S. Auden Schwartz?

|

||||

---------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

========================================================================================================

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[We offer this profile of our founder 15 years after its publication. Not one step back. Zana]

[We offer this profile of our founder 15 years after its publication. Not one step back. Zana]

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................

WHICH ISLAM? IN A PASSIONATE NEW BOOK, STEPHEN SCHWARTZ URGES AMERICANS TO RECOGNIZE THE BEAUTY OF ISLAMIC MYSTICISM - AND THE DANGERS OF OUR ALLIANCE WITH THE PURITANICAL SAUDI REGIME

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ SHOULD be used to this by now. Journalist and activist, historian, poet, and mystic, he's published 13 books, many of which excoriate the community of left-wing activists where he once sheltered. But this time something is different. His latest work, "The Two Faces of Islam: The House of Sa'ud from Tradition to Terror," a no-holds-barred attack on the Saudi fundamentalist creed known as Wahhabism, has made Schwartz the talk of the political talk shows and the toast of Washington's anti-terrorism crowd from William Kristol to Christopher Hitchens.

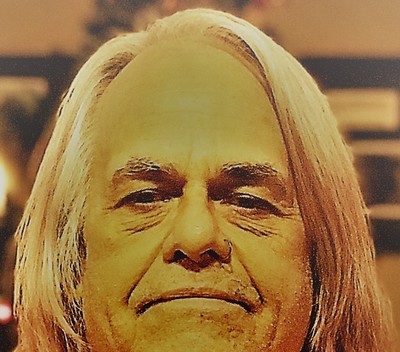

Schwartz, a voluble 54-year-old with a booming voice, a shock of white hair, and a flair for the dramatic, is loving it.

"I just debated Prince Turki!" he shouts gleefully into the phone to a reporter. He's just returned from the CNN studios to his office at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, an anti-terrorism think tank associated with a range of prominent conservatives, including Newt Gingrich. "People say to me, 'Great timing for your book,' " says Schwartz with a touch of contempt. "And I want to sit down with them and say, 'Let me explain to you how the world is. When you understand what's going on, and you've published a book the goal of which is to be the "Uncle Tom's Cabin" of the Saudi transformation and to unmask Wahhabism, it's not a matter of great timing. I wouldn't have done this if I didn't know the Saudis were going to help with the PR campaign, so to speak.' "

The Saudis seem to be working overtime on Schwartz's behalf. Since revelations about the Princess Haifa's possible connection to Osama bin Laden's terror network, the news media has been abuzz with one question, often phrased with a strange American ingenuousness: "Are the Saudis really our friends?"

Schwartz's answer is an emphatic "No." His book traces the founding of the Saudi state to a toxic alliance between the Sa'ud clan of desert bandits and a hate-mongering, literalist Muslim scholar by the name of Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, whose family married into the Sa'ud family in 1744. Although the resulting Wahhabi-Saudi alliance espoused a vehemently insular theology - they denounced as infidels those fellow Muslims who did not adhere to their sect - they also courted the favor of the great Christian powers in their contest with the Ottoman Turks. With the support first of Britain and later the United States, the Wahhabi Saudis eventually captured the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina and came to dominate the oil-rich Arabian peninsula.

Flush with US petro-dollars and US patronage, writes Schwartz, Saudi Arabia has channeled untold funds into anti-American and anti-Israeli terror groups and indoctrination efforts via its vast network of madrassas, mosques, newspapers, and publishing houses. Wahhabi Saudis view any celebration of the prophet Muhammad's birthday as a form of idolatry; they destroy decorated mosques and graves; they abhor music of all kinds; they reject modernity; and they proclaim the world to be divided into a sphere of their own believers and a sphere of war. Wahhabi incitements to violence against "infidels" stand in sharp contrast to the Saudi state's pro-Western policies. A deep crisis has resulted in Saudi society - one that came to a head on Sept. 11, 2001.

The Saudi state urgently needs to break with Wahhabi extremism, Schwartz argues, and to that end, the United States must demand a full accounting of the involvement of Saudi subjects and officials in the Sept. 11 plot. If the Saudis can't be persuaded that this is in their interest, writes Schwartz, the United States must issue some kind of ultimatum. Ultimately, Schwartz would like to see a parliamentary constitutional monarchy take root in Saudi Arabia. He has written in The National Review that "the Wahhabi dictatorship over Mecca and Medina must be overthrown," even suggesting an "international Islamic administration over Mecca."

. . .

Is Schwartz, who writes frequently for The National Review and The Weekly Standard, a right-wing zealot on an anti-Muslim crusade? Like many of his colleagues on the right, he's a religious man; and he shares the conservative view that American society has become too libertine and too secular. Though he declines to take a public stand on Israel-Palestine, he makes it clear in his book that he sees Arabs as almost exclusively responsible for that conflict.

And yet nothing gets Schwartz going quite like what he calls the "Islamophobia" of the right. Why? For one thing, it's personal. Schwartz, who is of mixed Christian and Jewish descent, is a Sufi. A mystical and contemplative practice that emerged approximately two centuries after the advent of Islam, Sufism prizes an inner search for enlightenment. In his book, Schwartz defends the tolerance and spirituality of traditional Shi'i and Sunni Islam as vehemently as he denounces Wahhabi extremism. But it's Sufism's ecstatic quality, as well as its insistence on the unity of the three monotheisms, that he finds himself drawn to as a seeker.

"I'm about breaking down barriers," says Schwartz. "I'm about not wanting to choose between the Christian and Jewish side of me. And now as a Sufi, people say 'What are you, Jew, Christian, Muslim?' I don't answer that question. I'm a Sufi."

Within the Muslim world, there's little love lost between Wahhabis and Sufis. And few readers are likely to mistake Schwartz's book for a detached examination of that divide. Like much of Schwartz's writing, "The Two Faces of Islam" is idiosyncratic and passionate, careening from passages of artfully narrated history to lyrical rhapsodies about the Bosnian landscape or Shi'ite high culture, to hotheaded invective that damns the very desert where Wahhabism emerged - along with all of its inhabitants, past and present.

This literary presence is not unlike Schwartz's physical presence: heady, over the top, full of bombast and emotion, channeling erudition through spirituality, personal psychology, and back again.

. . .

Is Schwartz's portrait of Wahhabism accurate? Natana DeLong-Bas, a research assistant at Georgetown University's Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, has just completed a dissertation containing the first comprehensive analysis of Wahhab's writings in a Western language. The texts reveal something surprising, DeLong-Bas says. Today's Wahhabi practice cannot claim the unbroken connection to the 18th century that Schwartz envisions. In fact, Wahhab was himself neither a literalist nor a chauvinist: He permitted Muslims to have contact and business arrangements with non-Muslims, and he advocated jihad only as a defense, when Muslims were under attack. He did not consider non-Wahhabis infidels, as today's Wahhabis do.

If Schwartz has the 20th-century realities right - the Saudi state religion preaches hatred, and it's been aggressively exported around the world by a supposed US ally - do these sorts of historical quibbles really matter? Only insofar as they reveal a greater diversity of religious and political belief than Schwartz suggests, both within contemporary Saudi Arabia and throughout the country's history, says Hussein Ibish, communications director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. After all, notes Ibish, Osama bin Laden and the moderate, modernizing Saudi crown prince Abdullah represent very different political agendas; does this mean that Abdullah is not a Wahhabi? "I think the man is still a Wahhabi," he says. "But there are shades here."

So has Schwartz made an important distinction among Muslims, or has he instead simplistically divided them into two camps - good and bad? The question is complicated by the fact that no group actually calls itself "Wahhabi": the term is used only by outsiders. Still, according to Michael Sells, a professor at Haverford College and an expert on Islamic mysticism, the label is useful because it designates a group defined by a unique set of beliefs - that Shi'ites and Sufis are not Muslims, and that visiting shrines and celebrating the prophet's birthday are un-Islamic. "There's only one group in the world that has that combination of exclusions," says Sells. "And it's really a radical set of exclusions, propounded with absolute certitude and an implicitly violent attitude toward other Muslims."

. . .

The odyssey that brought Schwartz to Washington and Wahhabism is as colorful and unique as anything in American intellectual life. Though he never finished college, Schwartz has what Sells calls "the erudition to have about five PhDs." He's proficient in nine languages, and his books have covered everything from the Spanish Civil War to the Albanian national movement. "He's a model of a public intellectual," says his longtime friend, hawkish Cold War scholar Ronald Radosh. Robert Collier, who worked with Schwartz at the San Francisco Chronicle, describes him as "an autodidact omnivore."

A red-diaper baby native to San Francisco, Schwartz inherited his parents' radical politics, but not their militant atheism. When he was eight years old, a neighborhood bookstore displayed a Bible in its window, turning a page each day; Stephen read most of it standing in front of that window on his way to school. By the end of his teenage years, he was steeped in the writings of Friedrich Engels, the Catholic mystic Raymond Lull, the Sufi philosopher Idries Shah, and the Surrealists. He wrote poetry. And by correspondence, he joined a Trotskyist group of Spanish exiles living in France.

In the late 1960s, Schwartz studied linguistics at Berkeley, but academic life did not agree with him. Nobody had told him, he says, that "in order to succeed you have to swallow everything you know and pretend that you don't know it all already."

Instead, he shipped out with the merchant marine, then worked in the longshoreman union, and then on the railroad for seven years, weighing freight cars and writing union pamphlets. Schwartz treasured his proletarian job, but he was also part of the circle of Beat poets around the City Lights bookstore. He wrote political satire for a magazine published by Francis Ford Coppola, managed a punk rock band called The Dils, and traveled to Spain as often as he could.

Schwartz left the railroad when he was 32, taking a job as the official historian of the sailors' union just as his allegiance to the political left began to crack. It started with Cuba, whose revolution Schwartz had supported in its early days, only to be bitterly disillusioned with Castroism. Determined not to make the same mistake with Nicaragua, in 1984 he endorsed the Sandinista defector Eden Pastora, who had joined the US-backed Contra movement. When Schwartz made these views public and took a job at a free-market think tank called the Institute of Contemporary Studies, he says, "Within a week, I lost all my friends."

A dark period followed. "He was seriously vilified by people he knew in San Francisco," says his oldest friend, Paul Nagy. Schwartz recalls a spate of harassment: "Posters, leaflets, poison-pen letters, crank calls, physical threats." He stayed in San Francisco because he had a son there from a broken marriage. And before long, he was offered a job at the San Francisco Chronicle by the paper's libertarian publisher.

"Everyone thought of him as a right-winger," says Collier, "which of course in many ways he was." So when the Newspaper Guild went on strike in 1994, some of its leftist members jeered that Schwartz would be the first to scab. Instead, Schwartz became the heart and soul of the strike, shouting into a bullhorn in the pouring rain, heaping abuse on scabs, strike-breakers, and management. "Steve and his bullhorn were the stuff that legends are made of," says Collier. "He was just a poet of scatological union radicalism out on the picket lines." To Schwartz, that performance was vindication of the deepest kind: Though he had broken with the left, he had proven to himself and his former comrades that he would not abandon the labor movement. Today he calls himself a conservative social democrat.

Throughout the 1990s, Schwartz was increasingly drawn toward the Balkans. He reported on the plight of the Sephardic Jews of Bosnia, found common cause with Bosnia's Muslims, and soon discovered a deep affinity with the Albanians of Kosovo and Albania, through both the Albanian Catholic community and the local Sufis. NATO's war in Kosovo, he says today, is the only war in his lifetime that he has supported. After the war ended, he lived in the Balkans for two years.

Returning to the United States in 2001, Schwartz was hired and fired by the Washington, DC bureaus of both the Jewish weekly The Forward and the government-operated radio station Voice of America. Former colleagues and employers describe Schwartz as uniquely erudite and brilliant, but also mercurial and abrasive.

After the VOA stint, Schwartz threw himself into writing his book on Wahhabism, a phenomenon he'd first encountered in the Balkans. During the Yugoslav wars, Saudi clerics tried unsuccessfully to establish a beachhead there, but Bosnian and Albanian Muslims, influenced by pluralistic Ottoman and Sufi traditions, rejected Saudi blandishments. The story struck a chord in Schwartz.

"Look," he says, "I've seen this over and over again. People who are desperate, people who are isolated, people whose lives have been crushed by everything that exists in society to crush people's lives. Something comes into their lives and gives them meaning, whether it's unionism or the overthrow of Somoza or the defense that the Bosnians mounted against the Serbs. And there's always somebody there to take it away from them. Whether it's the communists in Moscow or the Castroites in Havana or the Wahhabis in Saudi Arabia, there is always somebody there to take it away from them."

Such betrayals are the stuff Schwartz's opus is built on. And one thing he has never done is to describe them passively. "Stephen Schwartz is someone who perceives himself as a soldier in a gigantic battle between good and evil," says a former VOA colleague. It's a self-perception that ricochets between the grand and the grandiose. It's also what has him, the grandson of an evangelical preacher, alternately bellowing, whispering, and crying when he tells a reporter his life's story. To Schwartz, a militant and a believer for as long as he can remember, everything seems to hang in the balance now: not just the war on terrorism and the future of the Saudi state, but the soul of Islam.

When Robert Collier thinks of Schwartz, one moment during the 1994 strike stands out. It's 8 o'clock in the evening in the pouring November rain. Schwartz has brought his boom box to the picket line, playing Bosnian protest songs, Beethoven's "Eroica," and the Lithuanian partisans' anthem. A tunnel joins the Chronicle building to the Examiner building, and Schwartz has entered it with his boom box blaring the Spanish anarchist version of the "Internationale." Only Collier sees him there: "Steve, staggering in ecstasy" - dumbstruck by the explosively perfect acoustics. "It was a wonderfully wacky, gloriously off-the-wall, passion-filled moment that to me just sums up a lot of the best of Steve."

Related Topics: African-American Muslims, Albanian Muslims, Alevism, American Muslims, Balkan Muslims, Bektashi Sufis, Bosnian Muslims, British Muslims, Canadian Muslims, Central Asia, Chechnya, China, Deobandism, Dutch Muslims, European Muslims, French Muslims, German Muslims, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kurdish Islam, Kyrgyzia, Macedonia, Malaysia, Moldova, Montenegro, Muslim Brotherhood, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Pakistan, Prisons, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sephardic Judaism, September 11, Shariah, Shiism, Singapore, Sufism, Takfir, Terrorism, Turkish Islam, Uighurs, Uzbekistan, Wahhabism, WahhabiWatch receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid