|

|

Karel Teige

|

||||||||||||||

[In this text, our founder, Ashk Sylejman, returns to his enduring interests: Surrealism, Central and Eastern Europe, and the fate of Russian Communism. Our Ashk has a distinguished profile in this field. He is the translator into English of the Czech Surrealist Jindrich Heisler, was associated with Marie Čermínová Toyen in the Paris Surrealist Group, translated the leading Romanian Surrealist Gherasim Luca, his mentor, and hopes to publish studies of Miroslav Krleža, Branko Miljković, and Beqir Musliu. In the 1970s he published the Czech Surrealist philosopher Ivan Sviták in English, and encountered Jana Boková, the filmmaker who pioneered media examination of the case of the Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas in the 1990 documentary Havana supported by the BBC. Our Ashk is a true intellectual who fights for liberty worldwide. --  Zana.]

Zana.]

###

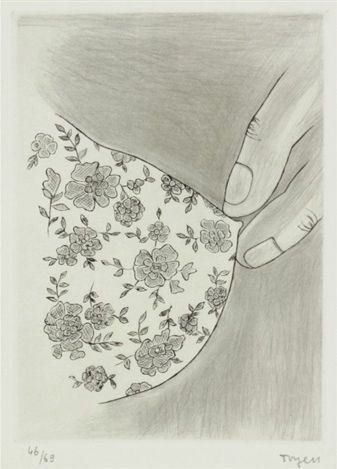

Toyen and Teige, 1925 |

Toyen. |

The death in Prague in 1951 of Karel Teige might best be described as cardiac arrest caused by heartbreak. Teige was then approaching his 51st birthday. In a city that had influenced and been influenced by European modernism throughout his life – think of the heritage of Alfons Mucha, Franz Kafka, and Frank Kupka – he had dreamed of artistic and political revolution. Brilliantly, he carried into new idioms the banner of French surrealism (with its attendant Trotskyism). Karel Teige by Rea Michalová is a valuable document revealing to the world a hidden history of artistic modernism and Stalinist reaction in Central-Eastern Europe.

Prague 1968. |

When he died Teige's influence extended throughout the flourishing avant-garde in Central Europe (while living in Sarajevo I read him in Slovene). But he perished as an outcast, isolated, threatened, silenced. The Stalinist regime in power in Prague considered a surrealist art critic a major menace to their order. And they were doubtless correct to do so, for the memory of Teige led to the Prague Spring of 1968 as well as the liberation of 1989, guided by such figures as the writer Milan Kundera and playwright Vaclav Havel. Commentaries on the previously-banned Joyce, academic work on the heritage of Kafka, and reprinting of the Czech surrealists epitomized 1968 in Prague, facing Russian tanks, no less than slobby, riotous hippies did the radical uproar in Chicago the same year. But the rebels in the East had little need of the hallucinogens to which those in the New World were drawn: the drug of choice in the socialist world was freedom, and that was quite enough.

Although Surrealism in its Czech iteration not only transformed verse in that language (and influenced it in Slovak), it faced a serious challenge after World War II, along with its manifestation in Romanian: could it defend democratic and modernist culture in a atmosphere of Communist militancy? The new generations in both countries had seen in surrealism a combative alternative to "socialist realism" during the Russian chill of the 1930s. This may be perceived as an absurdist fantasy. But just that outcome was realized in Titoite Yugoslavia.

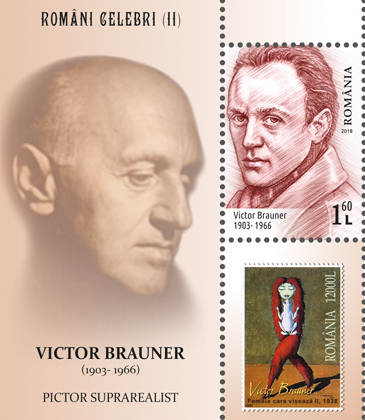

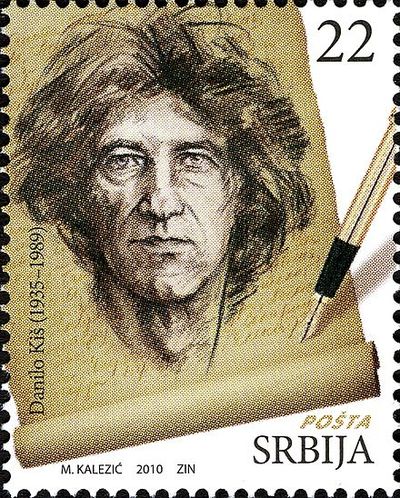

Companions of Teige included Jaroslav Seifert, Nobel literature laureate in the pregnant year 1984; in 1922 the two were expelled from Communist literary journalism together, for publishing in "bourgeois" media. That detail reminds one of the neo-Borgesian radical chronicles of the noted Serbian author Danilo Kiš (see my "Five Yugoslav Classics" in TNC, May 2000), reflecting the struggle of Central and East European leftist intellectuals to realize their dreams of popular cultural enrichment, destined typically to lead them to Auschwitz and the gulag. But the Bukovinan poet Paul Celan disproved the fraudulent enlightener Theodor Adorno's arguments in the name of the fossilized Thomas Mann and Arnold Schoenberg that European culture could not survive the Holocaust.

The Prague Linguistic Circle. |

The volume under review was assembled with Habsburg-style thoroughness. It records Teige's Protean involvement with nearly every dimension of modernist experiment, from architecture – perhaps his most authentic professional métier – to the researches developed by his neighbors, the Prague Linguistic Circle identified mainly with the Slavicist Roman Jakobson. Teige's ideas were never anything but original – in 1920, for example, his uniquely-inspired leftism led him to exalt painters of life over mere artists, holding Van Gogh superior to Cézanne, and the Douanier Rousseau in higher esteem than Picasso.

Rousseau. |

As an omnivorous mind in a legendary city of the imagination, a revolutionary feverish in his appetite for the unanticipated challenge, Teige symbolized Czechoslovak culture between wars as a force with which to reckon in Europe and the East. Teigean surrealism was erotic, hyperinventive, and socially acute. Teige promoted French writers, while his colleague Karel Čapek had given the world a new paradigm of alienation in the "robot," a concept derived from the common-Slavic word for labor. Perhaps because Prague bridged medieval and modern, its writers perceived the dangers in excessive experiment with the human. Prague produced the story of the golem, an animated clay figure created by Kabbalistic means to protect the ancient Jewry, but which ran amok; it conceived of the robot, a similarly inert instrument of alleged progress, which defeats its human inventors. Prague survived the marching minions of Nazism and Communism, with unique comprehension of its tragic destiny. But Teige and his peers could not give up Revolution.

The Old Jewish Cemetery, Prague. |

The Prague surrealists who gathered around Teige are as yet little known outside Central and East Europe, and naming them will have little resonance for readers, although this volume includes sufficient iconography to, one hopes, stir some interest in them. Teige's own output begins with evidence of unmistakable talent in watercolors and oils of Czech landscapes, done in his early teenage years, and continue with his discovery of photography and his self-proclamation as "the first Czech Cubist."

Teige, "Village," 1919. |

Teige's trajectory exemplified that of a provincial prodigy in a "devouring" development process. He had to know everything about art and politics, as well as their intersection in architecture and urban planning. The Czechs and other Central and East European nations had been held back by the long Habsburg twilight, in which they benefited from economic modernization, cultural tolerance, and a rich tradition of dissidence. As Breton noted, Teige was a worthy successor to the Bohemian religious reformer Jan Hus. Like Hus, Teige was an object of suppression, but also like Hus, whose persecution by Rome was vitiated in 1999 by the Polish Pope St. John Paul the Great, Teige represented an eternal hope.

Hus. |

Teige entered his Hus-like Calvary in May 1946, when the ascendant Czechoslovak Communist Party's Agitation and Propaganda Division "requested" a "written self-criticism." Teige had spent his entire life in self-interrogation and self-examination. Why add to this fruitful set of habits a perfunctory, ideological "confession?" An explanation is obvious: brutes had overrun Prague, not unlike the robots described by Čapek. When German imperialism subjugated the Czechs, the world paid attention. Czech resistance fighters were coordinated from London during the second world war. But after the war, the spirit of Chamberlain dominated the global horizon: Sovietism was perceived as permanent. It remained for the Czechs to regain their liberty on their own. The struggle was long and demoralizing; the Czechs were derided by the Titoite Yugoslavs as cowards who let the Germans and Russians subdue them.

Heydrich. |

The end of Czech modernism, for a generation, came with the execution of a Trotskyist literary critic and companion of Teige, Zaviš Kalandra. Kalandra was used absurdly in a proceeding aimed far and wide, with a net thrown out to implicate Slovak anti-Nazi heroes no less than enthusiasts of surrealism. Kalandra and three other defendants were executed in 1950. (They were rehabilitated in 1989, and Kalandra honored as a national hero.) But Teige's Prague was now a bastion of arbitrary oppression, reminiscent of Kafka's castle. Frightened, Teige was killed by his weak heart. The Communists did not need to arrest, frame, and slay him directly.

Kalandra. |

When Kalandra was done to death, Breton protested to the French poet Paul Eluard, a former surrealist turned Stalinist hack. David Lodge noted, in The Washington Post in 1992, how Kundera evoked this moment in modernism: the Czech novelist saw young Communists dancing in the streets to celebrate the purge, and imagined Eluard among them, "recit[ing] one of his high-minded poems about joy and brotherhood," in a ritual that causes the dancers to rise into the air. It is the fantasy in which all revolutionaries indulge, and by which Karel Teige and others vanished from the world. We will not see their like again.

# # #

Related Topics: Balkan Muslims, Russia receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid