|

|

Bosnian Cultural Heritage Under Peacetime Threat

by Stephen Schwartz http://www.islamicpluralism.org/1971/bosnian-cultural-heritage-under-peacetime-threat

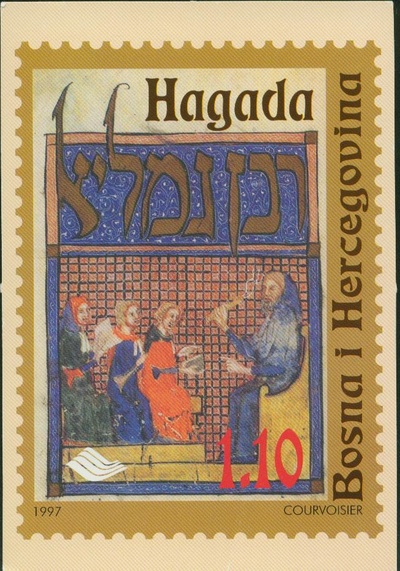

The war also encompassed the rape of tens of thousands of Muslim women and expulsion of two million people from their ancient homes. Atrocities were committed by members of all three contending ethnic groups -- Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks -- but, as reflected by the judgments of the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia in The Hague (ICTY), overwhelming responsibility for attempted genocide rested with the Serb side. The Serbs claimed to defend a Yugoslavia that had collapsed. Still, most emblematic of the onslaught on Bosnia's history was the systematic vandalism by Serbian forces of religious and cultural institutions, including the devastation of mosques and Croat Catholic churches. During the three-year siege of Sarajevo, some 12,000 residents, including more than 1,000 children, were killed by sniper and rocket fire from the Serbian military positions in the mountains surrounding the city. While bullets and missiles took people's lives, their heritage, including the output of four centuries of Ottoman rule in the country, was also subjected to attempted eradication. Cultural vandalism in the Bosnian war was chaotic and unpredictable, making an authoritative account of the depredations difficult. Different witnesses have told varying stories of what happened, but on some details there is unanimity. In Aug. 1992, Serb troops concentrated missile fire on the National and University Library, housed in the former City Hall in Sarajevo's old center, designed in the neo-Moorish style and erected by the Habsburg authorities ruling Bosnia-Herzegovina in the late 19th century. The resulting blaze continued for three days, and afterward the ashes of manuscripts and books fell on the city "like dirty black snow," in the words of the late Bosniak librarian Kemal Bakaršić. Losses are estimated at between 1.2 and 1.5 million books, of which some 155,000 were rare volumes or manuscripts. The institution also housed the national archives of Bosnia, record copies of Bosnian periodicals, and the library collections of the University of Sarajevo. Another major institution, the National Museum of Bosnia-Herzegovina, founded in 1888 by the Habsburgs, was close to the urban front line. The most famous item in the possession of the National Museum is the Sarajevo Haggadah, an illuminated text for reading at the family table in the Jewish Passover service, or seder, with extensive supplemental prayers and poems in Hebrew and Aramaic. The Sarajevo Haggadah is considered one of the most beautiful and valuable Jewish manuscripts in the world, with multicolored illustrations and gold leaf decorations. Thanks to National Museum and Bosnian Muslim officials, it was kept safe during the war, in the vault of the National Bank of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Sarajevo Haggadah was not created in Bosnia, but in Catalonia or Provence in the 14th century. After the expulsion of the Spanish Jews beginning in 1492, it was taken to Italy, where in the 17th century it was examined by a Catholic censor who added a written signature, presumably having found it inoffensive to Christians. It appeared in Sarajevo at the end of the 19th century and was sold to the newly-established National Museum. The Jewish manuscript was rescued previously from the Nazis, during the second world war, by a Catholic and a Muslim who worked at the museum. For Muslim Bosniaks as well as the surviving community of Bosnian Jews, the Sarajevo Haggadah is more than a Jewish sacred book. It is a symbol of the long history of mutual respect and cooperation between Muslim and Jewish residents of the city, and of common Bosnian identity. Sarajevo was founded in 1461-63, and in 1581 establishment of its first synagogue was authorized by Bosnia's Ottoman governors. Bosnian Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived in mixed communities, with no ghetto walls. Segregation of their communities began only in 1992. The Bosnian war ended with the Dayton Accords of 1995, which split the country into a Serbian "republic" and a Bosniak-Croat "federation," with a minimal central governing apparatus. The Sarajevo Haggadah, nevertheless, was returned to the National Museum and eventually installed in a controlled-temperature room. Now, unfortunately, the libraries and museums that were attacked in the 1992-95 war face a new threat. At the beginning of January, global media including the BBC, Associated Press and leading newspapers reported that seven Bosnian cultural institutions will shut down because of inter-ethnic disagreement over Bosnia's cultural patrimony, and lack of money. The country's National Art Gallery shut its doors last year, the Historical Museum and the National Library ceased receiving funds in January, and the Museum of Literacy and Theatre Art, National Film Archive, and Library for the Blind and Visually Impaired face closure. On Jan. 6, the "Bosniak-Croat Federation" authorities announced they would provide 25,000 euros to pay utility bills for the National Museum -- a meager and temporary solution, but one that will save the Sarajevo Haggadah a third time. Sarajevo has suffered a harsh winter and heat in the reading rooms of the reorganized National and University Library was cut off as its staff struggled to maintain its services to the public. But Sarajevans blame the problem, above all, on the refusal of the "Serbian Republic" to define a common cultural legacy with the "Bosniak-Croat Federation." As reported by Sabina Nikšić of the Associated Press: Bosnian Serbs, in particular, oppose giving the central government control over the cultural sites, with their leaders often insisting that Bosnia is an artificial state and that each of the country's ethnic groups has its own heritage. Bosniaks, meanwhile, insist that safeguarding the shared history of the Bosnian people is one way to keep the country unified instead of permanently splitting it the way many Bosnian Serbs would want. Reports on the crisis of Bosnian cultural institutions fail to mention an additional factor: the United Nations, the European Community, and other members of the "international community" delivered touching pledges, during and after the Balkan wars, to allocate money for reconstruction of cultural institutions in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In nearly 17 years since Dayton, few of these promises were realized. And now, with Western Europe as well as the Balkans in deep financial crisis, it may be too late. The erasure of Bosnian collective memory attempted by fire almost 20 years ago may be accomplished finally by political intrigue and neglect. Related Topics: Balkan Muslims, Bosnian Muslims, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Sephardic Judaism receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list |

Related Items Latest Articles |

||||

|

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism. home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid |

|||||