|

|

PUBLICATION NOTICE: The Bektashi-Alevi Spectrum from the Balkans to Iran

|

||||||||||||

This important contribution by the founder of the Center for Islamic Pluralism and the Second Bektashi Sufi Mission to America has been published by Routledge, the leading academic house. It is included in the volume Minority Religions in Europe and the Middle East: Mapping and Monitoring, Edited by George D. Chryssides. ISBN 978-1472463609, US$135.09 hardbound, available on Kindle. This is a basic teaching text for the Second Bektashi Sufi Mission to America.

Presented to the Inform Anniversary Conference, 'Minority Religions: Contemplating The Past And Anticipating The Future', at the London School of Economics, 1 February 2014.

This brief presentation, based on original field research, will describe the situation of the Albanian Bektashi Sufi order, the Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşi movement, and the Iranian-Kurdish Ahl-e Haqq phenomenon.

Haci Bektaş Veli, may his mystery be sanctified. |

I should note that notwithstanding the assumptions of some academics, I do not believe there is any historical or contextual link between these three groups and the 'Alawite' or Nusayri body that makes up the core of the present Syrian Ba'athist dictatorship and army.[1] I would add that given the mission of Inform to monitor cults it might have been more appropriate for me to present a paper to this conference on the cultism of the Syrian political apparatus. The Syrian war is often described in media now as a Shia-Sunni sectarian conflict, when in reality it is a war between the Nusayris, who are not Muslim and were never considered so before the 20th century, and the conventional Sunni majority in Syria.

Damage to the Great Mosque of Aleppo, Syria, inflicted by the Nusayri dictatorship. |

When I first conceived these remarks, I was impelled by a belief, based on my own observation, that the Albanian Bektashis, Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşi movement, and the Iranian-Kurdish Ahl-e Haqq formed a continuum of essentially-identical doctrines and rituals. But I have concluded more recently that they appear on a spectrum, rather than in a continuum, and that differences between them cannot be overlooked.

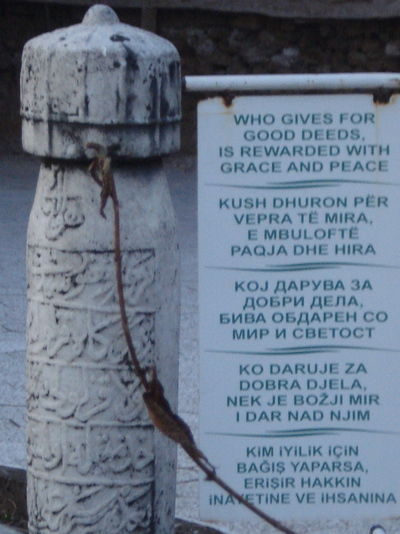

Bektashi Principles. Monument at the Harabati Baba Bektashi Teqe in Tetova, Republic of Macedonia -- Photograph 2010 by the Bektashi Community of the R.M. |

Recruitment of the yeniçeri remains a controversial topic. Many commentators, including some Muslim scholars, have accused the Ottoman state of exacting a 'blood tax' from the Christians over whom the sultans ruled, and forcing the yeniçeri to accept Islam – a contravention of specific divine guidance in Qur'an, which commands, 'Let there be no compulsion in religion. Truth stands forth from falsehood'.[2]

It has often been argued that the Bektashi Sufis, in their association with the yeniçeri, borrowed Christian customs to ease the path of the new Muslims into Islam. These 'Christian' vestiges included celibacy among certain Bektashi teachers, or baballarëve in Albanian, and drinking of wine and other intoxicants by some, but not all Bektashis. Further, the Albanian Bektashis are known for their historical good relations with Catholic and Orthodox Christians and with Jews. Their relations with official Sunni ulema have been more complicated, as will be seen.

Until 1826 the Bektashis were one of 12 'recognized' Sufi orders under Ottoman authority. But in that year the yeniçeri were suppressed, following demands by the Western European powers for the abolition of 'archaic' institutions and modernisation of the Ottoman state. Bektashi tekkes or meeting houses were taken over by members of the strictly-Sunni, shariah-centric Naqshbandi Sufi order, which, unlike the Bektashis, was notably hostile to non-Muslim religions.[3]

The Bektashi Sufis survived in clandestinity, regaining much of their influence in Turkey, until the general prohibition on Sufi orders by Mustafa Kemal, the architect of the secular Turkish Republic, 99 years after the first abolition of the Bektashis, in 1925. The Bektashi tariqa thereupon moved its world headquarters – the Kryegjyshata or 'Court of the Supreme Grandfather' – to Tirana in Albania.

Bektashi Kryegjyshata, Tirana, Albania. |

The Bektashis had established previously a significant presence in southern and central Albania, with close proximity to Albanian Orthodox Christians. Bektashi numbers were so great that until very recently they were counted as half of the Muslim 70 percent of citizens of Albania proper, but a new census of Albania, conducted in 2011 and released by the national Institute of Statistics, enumerated Bektashi affiliation at only 2.09 percent of the population, with self-identified 'Muslims' granted a 56 percent share. This low figure for Bektashis may represent only those initiated fully into Bektashism, while in my observation many Albanians declare themselves Bektashi by family heritage, even if they have never entered a Bektashi shrine or participated in the observances of the tariqa.

Still, in a national population of 2,821,977, a two percent Bektashi representation accounts for nearly 60,000 individuals, presumably adults. It should be noted further that the same 2011 census, which produced a total of 10.03 percent Catholics – a long-enduring share of the country's religious population – relegated the Albanian Orthodox to 6.75 percent, when Albanian Orthodox Christians were traditionally credited with twice the number of Catholics, or about 20 percent of religious believers.[4]

Albanian Bektashis are also prominent in Kosova and Macedonia, and provided many leading participants in the Albanian National Renaissance, or Rilindja, beginning in the 19th century under Ottoman rule. They and the Albanian Catholics became best known for advocating and organising education in the Albanian language, while Sunni Muslims favored education exclusively in Turkish – the official policy of the empire – and the Albanian Orthodox Christians were drawn to Greek-language education.

But the standing of the Bektashis in these three Balkan territories differs today. In Albania, the Bektashi Sufis have been recognized as a distinct Islamic community under the 'ambiguous... supervision'[5] of the official Sunni apparatus, with which they enjoy cordial relations. The Sunni ulema in Albania proper and the Bektashis appear in public life as equals, without the Bektashis seemingly subordinated to the ulema. Typically, the Sunni mufti of Albania, Skënder Bruçaj, speaks or walks together at official and religious observances with the current kryegjysh, or head, of the Bektashis, Haxhi Dede Edmond Brahimaj, who sometimes precedes the Sunni mufti.

In Kosova, the Bektashis and an alliance of Sunni Sufis, the Union of Kosova Tarikats or Bashkësia e Tarikateve të Kosovës (BTK), previously titled the Community of Aliite Islamic Dervish Networks, with the Albanian acronym BRDIA, are unrecognized and, in general, are ignored or disparaged by the official, fundamentalist-oriented Islamic Community of Kosova (known as BIK).

In Macedonia, the Bektashis are under violent pressure from the official Sunni, fundamentalist, and radical Islamic Religious Community of Macedonia (known as IVZ in Macedonian and as BFI in Albanian, both as abbreviations of the title 'Islamic Religious Community'). The Macedonian ulema are headed by a Macedonian Albanian Sunni cleric, Sulejman efendi Rexhepi. The Macedonian Sunni apparatus has usurped control of a significant Bektashi religious complex, the Harabati Baba shrine, founded in 1538 CE in the Western Macedonian city of Tetova. The Macedonian official Sunnis have engaged in a campaign of occupation and aggression against the Bektashis in Tetova.

In 2002, the Harabati shrine, one of the largest Sufi installations in the Balkans, was invaded and turned into a mosque by Sunni radicals. Bektashi teqet do not traditionally include the appurtenances of a mosque, such as a prayer niche indicating the direction of Mecca (mihrab), a minaret, or voicing of the adhan or call to prayer. The Sunni interlopers transformed a tower in the Harabati complex into a minaret by equipping it with loudspeakers, which sound the adhan regularly in the harsh, rapid-fire manner of Saudi-inspired Wahhabism. While women pray alongside men and sing Bektashi hymns in the Bektashi Sufi rituals, the Sunni intruders turned one of the buildings of the Harabati complex into a separate 'women's mosque'. At the end of 2010, the remaining buildings occupied by the Bektashis at the Harabati shrine were subjected to an arson attack.

Wahhabi arson damage at the Harabati Baba Bektashi teqe -- Photograph by the Bektashi Community of the Republic of Macedonia. |

On 25 March 2014, the European Commission on Democracy Through Law (the Venice Commission) found in the complaint of the Sufi Union of Kosova Tarikats regarding the policy of the official Sunni ulema of Kosova, 'There would appear to be a dispute within the Islamic Community about whether the [Sufi] community is a separate community. The Islamic Community representatives stated that it represents all the Islamic believers in Kosovo', including the Tarikats, even though the Tarikats express the wish to be registered separately. In this connection the Venice Commission refers to the Judgment of the Court in the case of the Metropolitan Church of Bessarabia and others v. Moldova, in which it stated: "in principle the right to freedom of religion for the purposes of the Convention excludes assessment by the State of the legitimacy of religious beliefs or the ways in which those beliefs are expressed. State measures favouring a particular leader or specific organs of a divided religious community or seeking to compel the community or part of it to place itself, against its will, under a single leadership, would also constitute an infringement of the freedom of religion. In democratic societies the State does not need to take measures to ensure that religious communities remain or are brought under a unified leadership." '[7] An appeal on this basis may serve the Macedonian Bektashis more effectively.

Alevi-Bektaşi cem. |

In a population of about 80 million Turkish citizens, the Alevis claim 20 million, or a quarter of the total, as well as about the same ratio in the Turkish diaspora communities of Germany, the Netherlands, and other Western European countries. This results in a total of as many as one million Alevi-Bektaşis in Germany alone. A recent and important book on Alevi identity by a German professor of comparative religions, Markus Dressler, titled Writing Religion: The Making of Turkish Alevi Islam[8] credits the Alevis with up to 15 percent of the domestic and diaspora Turkish population. This Dressler volume, the latest among several from his pen, nevertheless, betrays general ignorance of Bektashism in the Albanian lands. Dressler includes, additionally, references to claims by the academics Ahmet Yaşar Ocak and Ayfer Karakaya-Stump of a significant influence of the obscure Wafa'i (Vefai) Sufi tariqa on Alevi and Bektashi traditions. This alleged relationship appears unfounded.[9]

Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşi observances are markedly different from the Albanian Bektashi praxis of prayer and singing, which justifies, I believe, my projection of a Bektashi 'spectrum' in place of a 'continuum.' Alevi-Bektaşis gather for a ritual called cem, which begins with performance of music on the saz, a stringed instrument commonly employed from the Balkans to Iran, and continues with ecstatic dancing by women and men together. Alevi-Bektaşi dedeler or 'clerics' are not celibate in the manner of most Albanian Bektashi baballarëve. On the other hand, a considerable portion of Alevi-Bektaşis are endogamous, while Albanian Bektashi followers are exogamous. In addition, a small 'parallel' Turkish Bektaşi Sufi tariqa, which is disconnected from the Albanian Bektashis and is alienated from Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşi identity, stresses its rejection of endogamy. During the Young Turk movement of the early 20th century, which adopted the 'Jacobin' notion of a single Turkish identity for all subjects of the state, the Turkish Bektaşi Sufis opposed the assertion of Albanian nationhood by the Albanian Bektashis, and became hostile to the latter.[10]

Relations between the Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis and the Turkish Republic, both in its Kemalist secular form, and under the current, crisis-wracked Islamist regime of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development party (known as AKP), have been traditionally described by Alevis in terms of grievances. While the Turkish Republic was created with the appearance of a rigorously secularist state, it emphasized a single, unitary Turkish identity bound up with Sunni Islam, leading to the organization of religious life through the Presidency of Religious Affairs of the Turkish Republic or Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı, usually called simply the Diyanet.

The Diyanet supervises mosque construction throughout Turkey and in Turkish emigrant communities in Europe. It is strictly Sunni in doctrine and Turkish in its language, i.e. it accommodates neither Alevis nor Kurds. The Diyanet is financed by the Turkish state through taxation on all citizens regardless of their faith, with its 2014 budget projected at 5.4 billion Turkish lira, or £1.5 billion.[11] In 2011, the Diyanet was reported to control 85,000 mosques, which it staffs with imams who are civil servants. Between the AKP assumption of power in 2002 and 2011, the employees of the Diyanet grew from 74,000 to 117,541.

The Diyanet operates but does not own or build mosques, though it may contribute funds to their construction, which is typically carried out through the Diyanet Vakfı, or Diyanet Pious Foundation, an ostensibly-separate entity that holds many mosque property titles. The status of the Diyanet is anomalous in Turkish law.[12] But its power and its commitment to a single, Sunni interpretation of Islam is undeniable.

Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis complain that while the Diyanet assists and directs mosques, which it may build in Alevi-Bektaşi villages in Turkey where few or no conventional Sunnis reside, the Diyanet refuses to support construction of cemevi, or cem houses, where Alevi-Bektaşis meet to conduct their religious ceremonies. An opening to the Alevis by the Erdoğan government in 2007-2010 failed. This occurred because, according to Alevi representatives, the AKP would not address Alevi demands for either support by the Diyanet for the Alevi movement, or the abolition of Diyanet authority over religious affairs; recognition of the cemevi as 'houses of worship', and changes to the public school curriculum, in which Sunni Islam has been taught in classes on 'Religious Culture and Ethics', to include Alevilik and present it in a positive light. All such proposals have been rejected. According to Dressler, the Diyanet and the Turkish state have treated Alevilik as a trend within Sunnism, but as nothing more.

Alevilik in Germany, nevertheless, has status as a distinct 'religious community' from the local branch of the Sunni Diyanet, the Diyanet İşleri Türk-İslam Birliği; Türkisch-Islamische Verein der Anstalt für Religion e V. (Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs), or DİTİB. Alevilik is included in classes on religion and ethics in the public schools of five German states. Alevilik enjoys autonomous standing additionally in The Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, France, Switzerland and Austria.[13]

Like the Albanian Bektashis at the Harabati Baba shrine in Macedonia, Alevi-Bektaşis in Turkey have been subjected to threats and attacks. In the most notorious such incident in recent decades, a Sunni fundamentalist mob set fire to a hotel in which an Alevi cultural festival was taking in place in the central Turkish city of Sivas in 1993. The assault took the lives of 37 people, mainly Alevis, and has become a symbol of Alevi identity and oppression by the Sunni majority in 'secularist' Turkey. An earlier series of clashes and massacres, in 1937-38, involved the Turkish military suppression of the rebellious Kurdish Alevi population in Dersim/Tunceli, a region in eastern Anatolia.

Alevi demonstrators carry portraits of 1993 Sivas massacre martyrs, Kadiköy, Istanbul, March 31, 2012. |

Aggression against Alevi-Bektaşis in Turkey appears paradoxical in Dressler's accounting, in that exaltation of Alevi and Bektaşi cultural precedents, notwithstanding their strong Kurdish element, was an important aspect of the establishment of the 'Turkish History Thesis' propagated by the authorities of the Kemalist republic. This 'Thesis' aimed to reduce the importance of the Ottomans in the evolution of national identity and to strengthen the argument for a continuity of Turkish history beginning in Central Asia, with Alevi-Bektaşi spirituality reflecting a survival of shamanic influence.

Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis today are viewed less as a central component of a myth of national origins than as a bulwark of secularism against Sunnicentrism and Islamist ideology. In general, Alevi-Bektaşis support the Kemalist People's Republican Party (CHP), other leftist movements, and Kurdish national demands. Their situation within the Turkish state remains precarious. Their dissociation from the Ottoman tradition, given the strong neo-Ottoman tendencies within the government of Erdoğan and AKP, may cause worse problems for the Alevi- Bektaşis in the future.

The third group on which I will comment is the Iranian Kurdish metaphysical movement known as the Ahl-e Haqq or 'People of Truth'.[14] The Ahl-e Haqq do not reveal themselves publically, with few exceptions, and their numbers are unknown, but they may total from eight to 20 million adherents in an Iranian population of about 80 million. (These numbers have been challenged. Ahl-e Haqq demographics cannot be confirmed, first because of their concealment, and second because of the lack of transparency on such matters under the Iranian clerical dictatorship.) In this, they contrast with the Albanian Bektashis and Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis, who maintain extensive public activities, involved in political life and social service. Ahl-e Haqq consider themselves Iranian-Kurdish followers of Haci Bektaş Veli, and like the Albanian Bektashis and Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis, emphasize the equality of women in their rituals and structure.[15] They, like the Albanian Bektashis and Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis, believe the performance of music to be a form of worship. Indeed, if there is a 'continuum' uniting these three groups it is in their attachment to music as a means of sacred expression. Albanian Bektashis sing, Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis play the saz and sing, while Ahl-e Haqq perform on the tanbur, an instrument similar to the saz. For the Albanian Bektashis and Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşis, music is an element of devotion and attainment of transcendence, while for the Ahl-e Haqq it is the primary means of devotion.

Martin Van Bruinessen, a leading scholarly authority on all these groups, argues unequivocally for their common origin. He asserts that during the 13th-15th centuries CE, a stream of ecstatic and revolutionary mystics, the Qalandars, spread through the Muslim lands and 'their role in the formation of the Ahl-i Haqq, the Bektashi order, and the various Alevi sects can hardly be overestimated'. While the largest Ahl-e Haqq community is found in Iran, about 200,000 adherents to the tradition, Kurds known as Kaka'i, are concentrated in Iraq's Kirkuk Province, which lies just outside the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), to its south.[16]

Both as Iranian Kurdish Ahl-e Haqq and Iraqi Kurdish Kaka'is, this element of the Bektashi spectrum faces political and social persecution. Ahl-e Haqq identify as Shia Muslims and were supporters of the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979,[17] but in the intervening 35 years their standing as Muslims has been questioned by elements in the Iranian clerical regime. The most famous presumed martyr among the Ahl-e Haqq in the post-revolutionary period was the gifted and extremely popular traditional Sufi musician Seyed Khalil Alinejad, murdered at age 44, in exile in Sweden in 2001. The death of Alinejad has never been solved by the Swedish authorities, but Ahl-e Haqq leaders are convinced he was killed for refusing to accept the religious dictates of the Tehran theocracy.[18]

Seyed Khalil Alinejad, 1957-2001. |

In northern Iraq, where the majority of Kurds are Sunnis, the Kaka'is were ostracized and abused as allegedly outside Islam, and were targeted for murder by Sunni extremists after the 2003 U.S.-led intervention. Following the 2014 invasion of Syria and Iraq by the so-called 'Islamic State', which is sworn to wipe out heterodox Islamic as well as non-Muslim minorities, Kaka'is and their shrines are again under assault. A Kaka'i defense battalion was formed in February 2015 under the authority of the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq.[19] Resistance to the 'Islamic State' may provide Kaka'is, along with other Sufis, Shias, and anti-fundamentalist Sunnis in Iraq, new prominence and legitimacy.

Bektashism/Alevilik/Ahl-e Haqq, from the Balkans to Iran, is consistently identified with intra-religious diversity, social justice, and equality of women. For this reason, in places as disparate as Macedonia, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, the followers of a little-understood but much-loved Islamic mystic are victims of prejudice and violence. Their role in Islam and the changing nature of the global Muslim community or ummah should not be overlooked, for, as Dressler argued in his recent book, the histories of these groups are proof of the pluralistic nature of Islamic religious culture, which merits appreciation, and where possible, protection against radical Islam and the influence of the latter in politics.

[1] See, for example, the standard volume by Moosa, Matti, Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects, Syracuse, Syracuse University Press, 1988. The author treats the Nusayris as an ambiguous but clear variant of Shiism.

[2] Qur'an 2:256.

[3] See description of Bektashism in Schwartz, Stephen, The Other Islam, New York, Doubleday, 2008.

[4] See Njoftim per Media: Fjala e Drejtorit të Përgjithshëm të INSTAT, Ines Nurja gjatë prezantimit të rezultateve kryesore të Censusit të Popullsisë dhe Banesave 2011 (Press Release: Remarks By the Director General of INSTAT [Institute of Statistics], Ines Nurja On Presentation of Main Results of the 2011 Census of People and Housing), Tirana, INSTAT, n.d., at http://www.instat.gov.al/media/177358/njoftim_per_media_-_fjala_e_drejtorit_te_instat_ines_nurja_per_rezultatet_finale_te_census_2011.pdf, accessed January 2014. For an example of the prior numerical standard, assigning 45 percent of Muslims in Albania to the Bektashis, 20 percent of Albanians to the Orthodox Christian church, and 10 percent to the Catholic church, see the entry on Albania in Larkin, Barbara, ed., Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, Washington, U.S. Department of State, 2000.

[5] For this description of the relationship of the Bektashis to the Sunni clerical structure, see Doja, Albert, Bektashism in Albania: Political History of a Religious Movement, Tirana, Albanian Institute for International Studies, 2008.

[6] Documents in possession of Schwartz.

[7] See Strasbourg, 25 March 2014, Opinion No. 743/2013. European Commission For Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission) – Opinion On The Draft Law On Amendment And Supplementation Of Law N° 02/L-31 On Freedom Of Religion Of Kosovo – Adopted By The Venice Commission At Its 98th Plenary Session (Venice, 21-22 March 2014). Accessed at http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD%282014%29012-e, March 2015.

[8] The figure of 20 million is based on interviews by Schwartz with German Turkish and Kurdish Alevi-Bektaşi leaders. Reviewed by Stephen Schwartz, Middle East Quarterly [Philadephia, PA, USA] Fall 2014, accessible at http://www.meforum.org/4817/writing-religion-the-making-of-turkish-alevi-islam.Dressler's publication information is New York, Oxford University Press, 2013. Also see review by Stephen Schwartz, Middle East Quarterly [Philadephia, PA, USA] Fall 2014, accessible at http://www.meforum.org/4817/writing-religion-the-making-of-turkish-alevi-islam.

[9] A consultation with an outstanding Albanian Bektashi spiritual authority, Baba Mumin Lama of the Teqe in Gjakova, Kosova, on 23 February 2014, disclosed that the Wafa'i (Vefai) tariqa is unknown to Albanian Bektashis. This is significant in that Albanian Bektashis are generally very well-informed on the history of their tariqa.

[10] Dressler, ibid.

[11] See Baydar, Yavuz, 'Diyanet tops the budget league', Today's Zaman [Istanbul], October 20, 2013, at http://www.todayszaman.com/columnists/yavuz-baydar_329311-diyanet-tops-the-budget-league.html, accessed January 2014.

[12] See Yildirim, Mine, 'TURKEY: The Diyanet – the elephant in Turkey's religious freedom room?', Forum 18 News Service [Oslo], 4 May 2011, at http://www.forum18.org/archive.php?article_id=1567, accessed January 2014.

[13] See Sökefeld, Martin, Struggling for Recognition: The Alevi Movement in Germany and in Transnational Space, New York and Oxford, Berghahn Books, 2008.

[14] An extensive description of the Iranian Ahl-e Haqq is included in Moosa, Extremist Shiites, op. cit., but does not appear to this researcher entirely reliable.

[15] Schwartz, confidential interviews with Iranian experts on Sufism and members of Ahl-e Haqq living in Europe.

[16] Van Bruinessen, Martin, 'When Haji Bektash Still Bore the Name of Sultan Sahak,' in Popovic, Alexandre, and Veinstein, Gilles, eds., Bektachiyya, Études sur L'Ordre Mystique des Bektachis et les Groupes Relevant de Hadji Bektach, Revue des Études Islamiques, LX, fascicule 1, Paris, Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1992.

[17] Bruinessen, ibid.

[18] Schwartz, confidential interviews with members of Ahl-e Haqq in Europe. For background on Seyed Khalil Alinejad, see Schwartz, Stephen, 'The Enigmatic Death of an Iranian Émigré', The Weekly Standard Blog [Washington], January 21, 2010, at http://www.weeklystandard.com/blogs/enigmatic-death-iranian-%C3%A9migr%C3%A9, accessed January 2014, and Schwartz, 'Mourning a Beloved Iranian Sufi Singer, 10 Years Later', The Huffington Post [New York], November 30, 2011, at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/stephen-schwartz/mourning-seyed-khalil-alinejad_b_1115697.html, accessed January 2014.

[19] Salih, Mohammed A., Wladimir van Wilgenburg, 'Iraq's Kakai Kurds: "We want to protect our culture" ', eKurd [Vienna], 11 February 2015, accessed March 2014 at http://ekurd.net/iraqs-kakai-kurds-we-want-to-protect-our-culture-2015-02-11.

Related Topics: Albanian Muslims, Alevism, Balkan Muslims, Bektashi Sufis, Central Asia, European Muslims, Iran, Iraq, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Muslim-Christian Relations, Sufism, Turkish Islam receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Related Items

Latest Articles

© 2024 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid