|

|

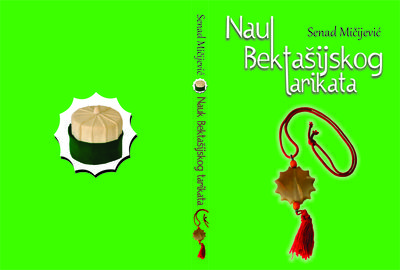

The Teachings of the Bektashi Sufis [Nauk Bektašijskog Tarikata (In Bosnian)]

|

||||||||||||||

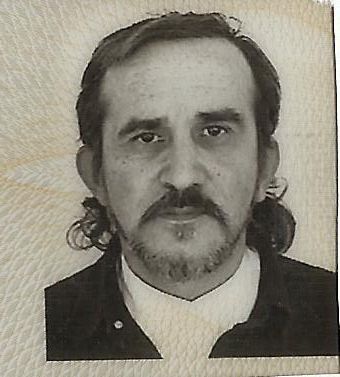

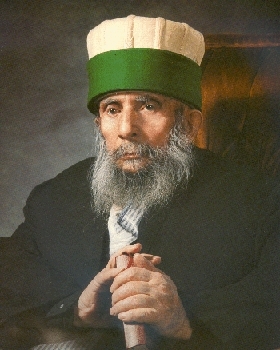

Rahmetli Senad Mičijević, 1960-2013. |

Senad Mičijević (1960-2013) was a resident of Mostar, the city in Bosnia-Hercegovina that, until the coming of war in 1992, was known for its multireligious coexistence. From then until 1995, Mostar was wracked by the aggression of Croatian and Serbian forces alike. The Croats were allied ostensibly with the so-called "Bosnian Muslim" fighters – the latter should better be called the soldiers of the Bosnian Republic, because they rejected a narrow religious identity.

But in their zeal to surpass the Serbian rebels in despoliation of the Muslims and others loyal to an ideal of Mostar's traditional identity, the Croats in 1993 destroyed the city's famous symbol, the 16th century CE Stari Most, or Old Bridge. The bridge had stood for 427 years. It was rebuilt and reopened in 2004.

Something remains missing, however, from today's Mostar. The so-called Muslim central district still exhibits the damage of war, and business recovery, for a town once renowned for its markets and tourism, has been slow. In Croatian-controlled territory, reconstruction has advanced markedly, along with entrepreneurship.

Senad Mičijević stood for the old spirit of Mostar, free and open. He opposed the infiltration of Wahhabi radicals into Bosnian Islam after the Serbian aggression in that country. He defended and documented the local metaphysical legacy of Islamic Sufism, and made a particular contribution in examining the stunningly-beautiful teqe (Sufi shrine and meeting house) at Blagaj in Hercegovina, one of several in the Balkans housing remains of the 13th century CE Bektashi Sufi saint Sari Salltuq. Another tyrbe of Sari Salltuq is located in the Albanian city of Kruja. The vicinity of Blagaj is notable in that it features additionally the significant Jewish monument to the 19th century Sarajevo rabbi Moshe Danon, who died in nearby Stolac in 1830, and a popular Catholic place of pilgrimage at Međugorje.

Sari Salltuq Bektashi Sufi teqe, 16th c. CE, Blagaj, Bosnia-Hercegovina -- Photograph 2009 Via Wikimedia Commons. |

His attraction to the Sufi legacy of Bosnia-Hercegovina led Senad to an inquiry into Bektashism. Although one of the 12 officially-authorized Sufi tariqats (orders) under the Ottoman empire, the Bektashi Sufis had been shrouded in controversy after they were attacked on a "reforming" pretext in the 18th century. The Bektashis were viewed by the Western powers as a bastion of Islamic obscurantism, since they were the chaplains of the yeniçeri or janissaries, the vanguard of the Ottoman army. Foreign interests demanded that the Bektashis and janissaries alike be suppressed, and so they were. Still, the Bektashis recovered with surprising rapidity. In reality, the Bektashis were anything but narrow Islamic believers or teachers. While powerful, they were Shia Muslims within the apparatus of a Sunni empire, and had a history of protecting heterodox Turkish and Kurdish Shia Sufis, known as Alevis or as Alevi-Bektashis.

The flag of the Bektashi Sufi order -- Illustration Via Flags of the World. |

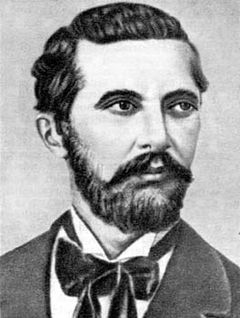

Nevertheless, the Bektashis were marked as Muslim dissenters, and following the secularization of Turkey in 1924, the Bektashis moved their headquarters to Albania where, distant from their Turkic and Persianate origins, they took on a specifically Albanian character. Previously, Albanian Bektashis exemplified especially by the Frashëri brothers, Abdyl (1839-92), Naim (1846-1900), and Sami (1850-1904), contributed to the education and reinforcement of the identity of the Albanians. In spiritual poetry, Naim expressed the national aspirations of the Albanian nation. He evoked the battle of Karbala in 680 CE, where Imam Husayn, grandson of Prophet Muhammad, was martyred. Sami Frashëri was also active as a Turkish enlightener. Many more Bektashis served the national and social needs of the Albanian people.

The flag of the Albanian nation. |

Naim Frashëri. |

To understand the foundations and practices of Bektashism, Senad Mičijević studied the Albanian language (he already knew Turkish) and travelled throughout the Albanian lands – Albania proper, Kosova, Western Macedonia, and other territories – as well as in Bulgaria and Greece, recording the names of the "babas" heading the teqet established there, photographing the buildings, and describing their histories. To do this, and in a demonstration of the true Mostar spirit of neighborly relations, Senad learned Albanian. His book is therefore a fit companion, especially in its geographical list of Bektashi installations, to the authoritative volume of Jashar Rexhepagiqi, Dervishet dhe Teqetë në Kosovë, në Sanxhak, dhe në Rajonet Tjera Përreth (Dervishes and Teqes in Kosova, in Sanxhak, and in Other Surrounding Regions)[1].

His love for and zeal to commemorate the Bektashis led him to be called, informally, "Baba Senad." His work emerged from a Slavic Muslim background under the rule of Yugoslav Marshal J.B. Tito, in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Serbia (including, then, Kosova), Montenegro, and Macedonia, that was hostile to Sufism. Socialist Yugoslavia was never as antireligious as Albania under Enver Hoxha, where all spiritual life was made illegal in the "world's first atheist state," but the Yugoslav Muslim Sunni clerics (ulema) dedicated themselves to stifling the Sufis.

Isa Blumi, in his Political Islam Among the Albanians[2], describes the campaign by the Titoite state "to confine legitimate power within 'the Islamic community' to a specific group of Muslim leaders (ulema) who were designated by Belgrade [the capital of Serbia and Yugoslavia] to represent all of Yugoslavia's Muslims...[S]uch a measure... cynically empowered Bosnian Slav Muslims... to disseminate a centralized (read Slav-centric) and homogeneous Islam throughout the regions where Yugoslavia's non-Slav [Muslim] populations (Albanians, Turks, and Roma) lived."

Continuing, Blumi's study notes, "the problems for Belgrade and their Bosnian allies based in Sarajevo was that the 'Islamic community' was not at all coherent... Islam had reached the Balkans by way of roaming spiritual leaders (shaykhs) who proselytized in rural areas among the Christian Albanian and Slav populations of the late Medieval period. These shaykhs were invariably attached to Sufi orders... For this reason, Kosovo was until the 1998-99 war a unique place to study the diversity of human spirituality... since most of these Sufi orders still practiced in the original village mosques from where they were established in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. The practices of these Sufi orders were uniquely local and reflected a spiritual tolerance... that was largely condemned by the Serb, Greek, and Sunni Islamic institutions of the late nineteenth century. By the end of World War II... only in Macedonia and Kosovo [did] these 'unorthodox' practices remain."

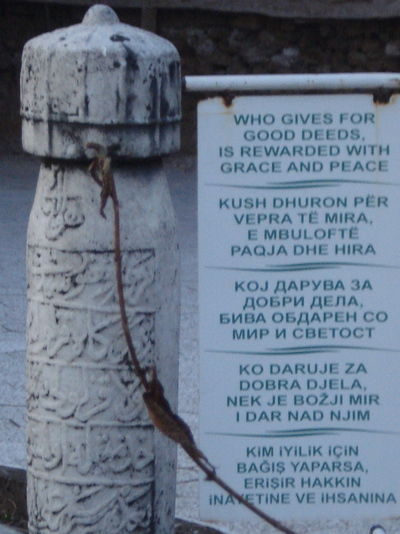

Bektashi Principles. Monument at the Harabati Baba Bektashi Teqe in Tetova, Republic of Macedonia -- Photograph 2010 by the Bektashi Community of the R.M. |

Blumi's analysis compares the past, Titoite assault by "official Muslims" on Kosovar Albanian Sufism with the invasion of Kosova by Saudi-Wahhabi fundamentalist preachers in the aftermath of the 1998-99 war. In both instances, a foreign (Slav or Arab) Islamic power attempted to impose itself on a deeply-rooted and hardy strain of Islam that reflected specific local conditions and the persistence of positive, pluralistic attitudes. Although his report was published in 2005, Blumi even predicted the minor but harmful participation of Albanians in the terrorism of the so-called "Islamic State" [ISIS], warning, "in ten years' time when war breaks out somewhere in the 'Islamic World,' local Albanian loyalties will be challenged."

This, then, is the panorama against which "Baba Senad" set out to reintroduce Bektashism to Bosnia-Hercegovina – since it was certainly known there in Ottoman times. That country, as noted previously, also underwent a substantial Wahhabi campaign of infiltration during and after the 1992-95 war. The Bosnian scholar of Sufism Saeid Abedpour, writing in the Sarajevo daily of record, Oslobođenje, a week after Senad's death in 2013, recalled, "In the years when the friendship and fascination of certain officials of the Islamic Community of Bosnia-Hercegovina for petrodollars greatly aided the spread of Wahhabi ideas, criticism by Senad Mičijević, and later by Rešid Hafizović and Mustafa efendija Spahić, was branded as dangerous and treated as a threat to the unity of the local Muslims."

"Baba Senad" demonstrated perhaps the most important Albanian influence on him in his steadfast refusal to bend to fundamentalism. Abedpour's obituary for him adds, "Senad, after the Bosnian war, failed to gain employment at any of dozens of cultural, educational and scientific organizations and institutions. Society simply does not appreciate such people, who do not belong to any party, interest group, or influential family coterie or gang. It did not matter that he was one of the cultural and intellectual pillars of Mostar."

His account of Bektashism was many years in preparation, but, sadly, he did not live to see its publication. The Teachings of the Bektashi Sufis is unique in the Bosnian-language bibliography on Islam for its theme, but there is no book in Albanian, much less English, so broad in its treatment of the Bektashis. Senad's writing begins with a preface by his editor, the Bosnian Sufi scholar Samir Beglerović, that evokes Muhammad, as is appropriate for any Islamic effort, but then touches on the early apostles of Islam among the Turkic peoples, Hoxha Jesevi and Arslan Baba. They and other mystics prepared the way for the appearance of Haxhi Bektash Veli (1248-1337 CE).

Haxhi Bektash Veli, may his mystery be sanctified. |

Senad presents the personal mystical ancestry (silsila) of Haxhi Bektash, then provides a thorough inventory of the teachings and practices of the Bektashis. He accomplished a complete journey through the Bektashi teqet, with photographs of many of them and their babas. Senad's book is a source of inspiration in that many of the teqet have been reconstructed in outstanding architectural form since the end of Albanian and Yugoslav Communism. The catalogue of images assembled by Senad assures that the Bektashis cannot be extirpated from the collective memory of Balkan Muslims.

The reconstructed Baba Qazim Bektashi shrine and library, Gjakova, Kosova -- Photograph 2007 Via Wikimedia Commons. |

Further, Senad reviews the activities of the Bektashi congresses, the organizational structure of the tariqat based in Albanian geographical zones, and the involvement of numerous babas and Bektashi disciples – some of them martyred –in the antifascist struggle against Italian and German imperialism. He recalls that Ahmet Ahmetaj Miftar (1916-80), who fought, like other Bektashi babas, in the Partisan army under Enver Hoxha, was named Kryegjysh ("Supreme Grandfather") as head of the Bektashi world community, in Tirana in 1948. But, predictably, given the ferocious hatred of Hoxha for religion, Baba Ahmet Miftar was interned in Albania with Baba Reshat Bardhi, who was born in 1935. Baba Ahmet Miftar died in a Communist forced-labor camp, as one of a long roster of Bektashi divines done to death by the Communist rulers. Yet Baba Reshat Bardhi survived and after the fall of the totalitarian state, became Kryegjysh, serving until his death in 2011. He was succeeded by the current Kryegjysh, Baba Edmond Brahimaj.

Rahmetli Baba Rexheb Beqiri, may his mystery be sanctified. His blessed example is always present for his disciples. |

The Hercegovinian acolyte has also given appropriate attention to the path-breaking work of Baba Rexheb Beqiri (1901-95), author of Misticizma Islame dhe Bektashizma (The Mysticism of Islam and Bektashism), published in English in Italy in 1984 and in Albanian in Tirana in 2006. Baba Rexheb's guide for the mystical seeker deserves a far wider distribution than it currently encompasses. But the small readership for Baba Rexheb's classic reflects how little known and, perhaps, even less understood Bektashism remains outside the Albanian culture area. "Baba Senad" likewise recounts, appropriately, the foundation by Baba Rexheb of the First Albanian Bektashi Teqe in Taylor, Michigan, USA, in 1954.

At the teqe in Taylor -- Photograph by Stephen Schwartz. |

Senad's treatise on Bektashism ends with memorial poems, but I consider it fitting to conclude this review with words from his funeral, delivered by the Mufti of Mostar, Seid efendija Smajkić. The Mufti said, "Senad, since early childhood, from his completion of Islamic primary school, showed great interest in questions of faith. Throughout his life he was dedicated to investigating and writing about our cultural history and faith."

Bektashism has generated a great quantity of valuable literature, printed and as manuscripts inventoried by "Baba Senad," in Albanian, English, Turkish, and other languages, expounding its principles and comprising commentaries by experts on Sufism, comparative religion, and Albanian society. This posthumous achievement is genuinely encyclopedic and will prove, I think, a necessary addition to every library of Islamic and Balkan studies. It merits translation and publication in Albanian, English, and other languages.

[1] 2nd., expanded ed., Dukagjini, Peja, 2003.

[2] Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development, Prishtina, 2005.

Related Topics: Albanian Muslims, Alevism, Balkan Muslims, Bektashi Sufis, Bosnian Muslims, Central Asia, European Muslims, German Muslims, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kurdish Islam, Macedonia, Montenegro, Muslim-Christian Relations, Muslim-Jewish Relations, Sephardic Judaism, Shiism, Sufism, Turkish Islam, Uighurs, Uzbekistan, Wahhabism, WahhabiWatch receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free center for islamic pluralism mailing list

Latest Articles

© 2025 Center for Islamic Pluralism.

home | articles | announcements | spoken | wahhabiwatch | about us | cip in the media | reports

external articles | bookstore | mailing list | contact us | @twitter | iraqi daily al-sabah al-jadid